WOMEN YOU SHOULD KNOW IN WYOMING: Game Warden Protects Wildlife, Teaches Hunting Skills

Kim Olson brings decades of experience, passion for wildlife to her job with Wyoming Game and Fish

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Mar 01, 2023

By Elizabeth Sampson

Special to the Wyoming Truth

Kim Olson has given plenty of ride-alongs to people interested in learning about her job as a Wyoming Game and Fish game warden. Only one ended in her untimely “death.”

Wyoming author C.J. Box rode along with Olson before writing “Wolf Pack,” the 19th book in his Joe Pickett series about a Wyoming game warden. In the novel, Pickett teams up with a female game warden based loosely on Olson, and—spoiler alert—the character ends up dead.

“It’s interesting to me looking back on it and knowing how our ride went, and then seeing what [Box] put in the book,” she said.

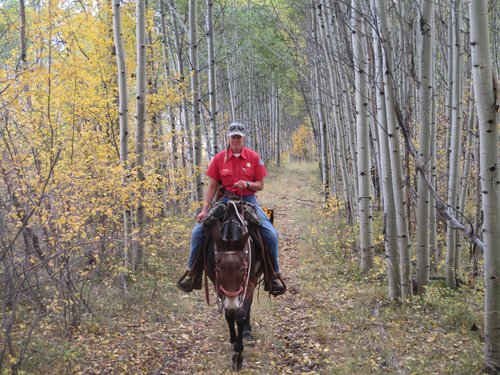

Olson 53, has worked for Wyoming Game and Fish for 18 years — the last 12 in Baggs —so she had plenty of insights and anecdotes to share with Box. As a game warden, Olson patrols her district, ensuring hunters and fisherman obey state laws and regulations, such as hunting in season with a license, properly tagging a harvested game animal or adhering to fishing creel limits.

Olson treats people with fairness and respect, as she recognizes that sometimes hunters make an honest mistake and believes it’s the best way to handle her law enforcement duties.

But when hunters intentionally break the law? “You can’t be afraid to ruin people’s days,” she said. “There are days when people are going to be unhappy with you, and it’s part of the job.”

Olson recalled a hunter who shot a moose, thinking it was an elk. The hunter abandoned the moose carcass, letting it go to waste.

In another situation, a husband-and-wife team harvested an elk and took it to Cheyenne for processing. Then they claimed they had lost their elk tag and purchased another one.

Gathering enough information to determine what the couple was doing required Olson to interview other hunters who had been in the area, including some who reported wasted elk meat the pair had left behind.

“I don’t know how many people I visited with over the course of that time…” she said. “You never know what you are going to come across or how it’s going to go unless you keep digging.”

Solving cases like these is one of Olson’s favorite parts of the job. “When you make some good cases — when you actually catch the folks who are doing bad things to wildlife —those are high moments,” she said.

Todd Graham, Green River Region Wildlife Supervisor for Wyoming Game and Fish, applauds the way Olson handles tough situations.

“As a game warden, you deal with all kinds of people and difficult issues, not only in law enforcement, but in wildlife management,” Graham said. “Having that even temperament and common-sense approach to her job is an asset.”

Graham often assigns young women to do ride-alongs with Olson to get a firsthand look at the job. “The fact that she’s a woman and has been doing it for a long time—and it hasn’t always been a woman’s career—really inspires women in particular,” he said. “In my mind, she’s a real inspiration for anyone who wants to be a game warden…”

Educating people a job perk

As a girl, Olson aspired to be a forest ranger, and spending time in the mountains, after her family moved to Cheyenne from Wisconsin when she was 10, solidified that dream.

“The first time I saw the Snowy Range I was hooked,” she said.

The wildlife management joins law enforcement aspect of the job attracted Olson to the game warden profession. She earned a degree in biology with a concentration in wildlife from Jamestown College in N.D., and then worked as a game warden, or conservation officer, in Utah for nine years before joining the Wyoming Wildlife and Fish Department in 2006.

Olson took up hunting in her 20s, and her late start, she said, gave her the maturity to make good decisions. Her two adult daughters are now both hunters themselves.

She enjoys teaching children’s programs and hunter safety courses—opportunities that allow her to share hunting skills, along with “the idea of hunting as management.”

“This is how we maintain the wildlife we do have,” Olson said, “and how we continue to keep the resources we have without it overburdening the habitat.”

Wardens also are involved in biology projects like gathering data for setting hunting seasons, doing antelope classification by truck or gathering data for the sage grouse leks, where those birds perform their mating dances.

Wildlife management does have its downside, though.

“When we get into the job, one of the things that nobody maybe mentions is the amount of wildlife we have to put down,” Olson said. “You’re the one who gets all the calls for every injured critter on the planet—whether that is an eagle, deer and antelope, or even the odd duck or bird in the backyard. You are the one who has to assess whether it will make it or not and deal accordingly.”

Olson is one of only a handful of female game wardens in Wyoming, but she hasn’t faced much pushback.

“There’s definitely still a few people that you can tell right away are going to blow you off because they don’t think you know anything or that you can’t do this job,” she said. “A lot of people don’t see it one way or another. They are just looking for knowledge.”

Olson recalled one group of hunters who sought her expertise in finding elk. When she returned to their camp later, the man said he got an elk where she suggested. He told her that he asked his hunting buddies if any of them had ever sought Olson’s advice—and none had.

“He [told them], ‘Well, next time do, and listen to what she says,’” Olson said with a laugh.

As for the ride-along that ultimately led to her fictional death, that, too, Olson takes in stride. When “Wolf Pack” was published, she met a local man at the post office who realized the female game warden character had experiences based on her. The man noted that things didn’t end well for Olson in print, and she laughingly agreed.

“He said, ‘Well nobody’s too good to die in a C.J. Box book,’” Olson said.