Lawmakers Explore Bipartisan Measures to Promote Economic Development on Tribal Lands

Chairing her first subcommittee hearing, Rep. Harriet Hageman highlighted bureaucratic barriers to tribal industry

- Published In: Politics

- Last Updated: Mar 02, 2023

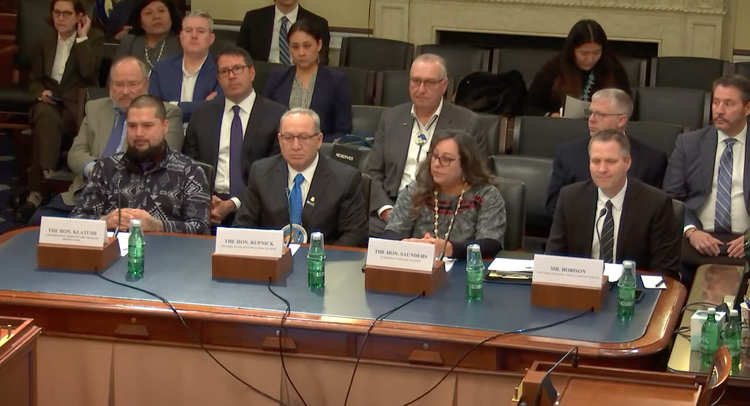

Rep. Harriet Hageman (R-Wyo.) oversaw her first hearing as chairwoman of the Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs Wednesday, exploring barriers to economic development on tribal lands. (Photo via YouTube / House Natural Resources Committee)

By Jacob Gardenswartz

Special to the Wyoming Truth

WASHINGTON — Lawmakers on the U.S. House Natural Resources Panel’s Subcommittee on Indian and Insular Affairs assembled for their first hearing of the 118th Congress on Wednesday to highlight long-standing barriers to economic development on tribal lands, kicking off a new bipartisan push to promote sovereignty for Indigenous Americans.

The hearing, entitled “Unlocking Indian Country’s Economic Potential,” served as the first formal opportunity for Rep. Harriet Hageman (R-Wyo.) to step into her role as chair of the subcommittee, and proceeded absent the fireworks and partisan animus that have consumed some of her other committee work to date. Lawmakers of both parties congratulated the Wyoming congresswoman for her appointment to the chairwoman role and pledged to work in a bipartisan manner moving forward.

But Hageman comported herself without any sentimentalities. After calling the hearing into order, she quickly detailed the legal system governing ownership of tribal lands, noting current policies frequently prevent local leaders from making important decisions “without the approval of Washington bureaucrats.” Such a process “can slow or in some cases halt development for years,” Hageman argued.

According to the Congressional Research Service, the vast majority of tribal lands are currently held through one of three ownership structures: “Fee lands” are owned entirely by Native American tribes or individuals and subject to many of the same rules and requirements as other types of privately-owned land, including state property taxes.

“Trust lands” are owned by the federal government, but held in trust for the benefit of the tribal community or individual members. Such lands are immune to many state and local laws, and those residing on them are typically not required to pay state property taxes.

“Restricted fee lands” function as a blend of the two previous categories, enabling tribes to maintain ownership of the land while still preventing the sale or encumbrance of those parcels.

Each ownership structure brings its own benefits and drawbacks, but tribal leaders present at the hearing all agreed: the current system needs to change.

“Frankly, what the government has done to us in our lands has been nothing more than to create a mess,” Joseph Rupnick, Chairman of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation, testified to the subcommittee. “The federal government should be able to protect our lands against sale and external taxation and regulation, not management or interference with our tribal governments land use decisions.”

Bureaucratic red tape dooms development

With the majority of tribal lands currently held in trust, all development efforts are subject to the approval of various state and federal government agencies, a process that often takes months or years. Most requests to change the ownership type of tribal lands require an official act of Congress, meaning all land development must be placed on hold while the notoriously-slow legislative body moves to approve the transfer.

Such a delay often dooms the prospect of development altogether, witnesses testified. “The more time that pass[es], the more likely that outside businesses will lose interest or look elsewhere,” said Dustin Klatush, Chairman of the Confederated Tribes of the Chehalis Reservation in Oakville, Wash.

As such, lawmakers stated their intent to amend the transfer process to reduce the red tape required to promote business development. On Tuesday, Hageman introduced the Long Term Leasing Act, a bill which would allow all federally-recognized tribes to authorize leases of up to 99 years for lands held in trust. The legislation, a draft of which was obtained by the Wyoming Truth, was referred to the Natural Resources Committee. Lawmakers of both parties indicated interest in that legislation during Wednesday’s hearing, though no further actions have been scheduled on it so far.

Infrastructure a key concern

It’s not just the unique ownership structures that have stifled economic development on tribal lands. Complicated regulatory frameworks make repairing already-crumbling infrastructure another key barrier, especially in more rural areas where transportation is already limited.

“The remoteness of our reservation and the extremely poor conditions of our roads are significant barriers for both tribal members and internal partners who otherwise want to develop businesses in our communities,” testified Wavalene Saunders, Vice Chairwoman of the Tohono O’odham Nation in Sells, Ariz.

“Deficiencies in transportation system infrastructure in Indian Country diminishes opportunities for development, which further impairs the ability of tribal communities to thrive,” she added.

As an example, Saunders highlighted her struggle to coordinate the repair of several roads near her tribe’s home on one of the largest federally-recognized reservations in the country. Due to liability issues and the intricacies between state and federal ownership of the land, Saunders said she’s been prohibited from pursuing basic fixes for potholes and cracks, leading to further deterioration of their condition.

Democrats on the committee, including ranking member Rep. Teresa Leger-Fernandez (D-N.M.), highlighted the $13 billion earmarked for tribal communities in the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law last year, though they noted such efforts were “not a silver bullet.”

But all lawmakers agreed more action was needed to promote tribal sovereignty and enable economic development.

“Land is the most important resource you have for economic development, for social [and] cultural issues,” said Rep. Jenniffer González-Colón (R-P.R.). “And when you got all those restrictions, there’s no way you can succeed.”