THE SEARCH FOR IRENE: What’s Next in Investigation of Missing Kenyan Nursing Student?

Legal experts weigh in on the difficulty of prosecuting cases without a body

- Published In: Criminal Justice

- Last Updated: Apr 11, 2023

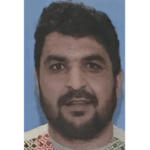

Gillette criminal defense attorney Steven Titus said no-body convictions are hard to secure, but not impossible. (Courtesy photo from Steven Titus)

By Jennifer Kocher

Special to the Wyoming Truth

GILLETTE, Wyo.—It’s been 14 months since Irene Gakwa vanished without a trace. The only “person of interest” in her mysterious disappearance, as identified by police, is sitting in the general population at the Campbell County Detention Center and awaiting sentencing in June after admitting to stealing nearly $6,000 from Gakwa and deleting her email account after she went missing.

That person is Nathan Hightman, 39, who has maintained his innocence in her disappearance, saying Gakwa left the couple’s home in northern Campbell County of her own accord in February 2022, exiting into a dark-colored SUV with her belongings packed in two plastic bags. Hightman has not been charged in Gakwa’s disappearance.

Before her disappearance, Gakwa spoke to her parents in Kenya every day. Her family is adamant that if Gakwa were still alive, she would have contacted them.

Gakwa’s body has not been found. There are no suspects as the Gillette police continue to investigate. So far, police have kept a tight lid on their investigation, releasing only a few cryptic clues. Last May, police asked the public to report any sightings of a silver-colored Subaru Crosstrek that might have been seen trespassing on private property between Feb. 24 and March 20, 2022, as well as any information about a 55-gallon metal drum that might have been burned or abandoned within the county.

Without a body, to what extent is it possible to file a murder charge? This question applies to any and all missing persons cases—not just the Gakwa case.

‘You only get one shot’

A no-body homicide conviction is difficult, but not impossible, according to Gillette criminal defense attorney Steven Titus. (Titus initially represented Hightman in his financial and intellectual property felony case until Hightman lost his IT job and retained a public defender.)

For the state to secure a conviction, it must prove that the victim died by a criminal act, in a particular jurisdiction and at the hand of a particular person or persons, he said.

“In Wyoming law, it’s up to the state to prove jurisdiction if someone is charged with a crime,” he said. “. . . If they can’t prove jurisdiction, the jury is advised to acquit.”

Without a body or physical evidence, the state doesn’t know which charge to bring, whether first- or second-degree murder, which further complicates the situation, Titus noted. Add to this the lack of physical evidence to determine a murder even occurred, let alone a manner of death.

There are scant stats to cull from, but to Titus’ knowledge, only two homicides without a body cases have been successfully tried in Wyoming.

The first involved the murder of Lynn Bush, 26-year-old Casper resident. Bush was initially reported missing in December 1990 by her husband David Labon Bush, who was eventually charged with her murder in 2006.

David claimed that his wife said she was going to a local grocery store but never returned. He further stated that the next day he found her vehicle in the store parking lot with the driver’s side door ajar and keys lying on the ground nearby, according to court documents.

After searching David’s pickup truck, police found what appeared to be blood stains spattered throughout the cab and on the passenger side of the vehicle. Police also found a vodka bottle in the couple’s home with what appeared to be blood on it.

Advanced DNA testing of the blood evidence in 2006 determined the blood was “probably that of Mrs. Bush,” according to court documents. Other evidence included statements made by the couple’s 4-year-old daughter to her counselor and psychiatrist indicating her father’s culpability in her mother’s death.

This was sufficient enough for the state to bring charges against David in 2007. A jury in Natrona County District Court ultimately found him guilty of second-degree murder, and he received a sentence of 45 years to life.

The second guilty conviction was Gerald Uden, who in 2013 admitted to killing his ex-wife, Virginia Uden, and his two adopted sons, 10-year-old Reagan and 11-year-old Richard, in Riverton in 1980. Their bodies were never recovered, and in 2019, Uden unsuccessfully attempted to recant his confession. He’s currently serving a life sentence for three counts of first-degree murder.

Titus said prosecutors need to be judicious in potentially bringing charges in a no-body case, because, baring a confession or physical evidence, they must prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

“You only get one shot at this thing,” he said.

High bar, but not impossible

From the late 1800s to present, 578 murder cases without a body have been tried throughout the United States, according to Thomas “Tad” DiBiase, a former assistant United States attorney in the District of Columbia who successfully tried a no-body homicide and tracks them on his website. Of those, 502 resulted in convictions and 76 resulted in dismissals, mistrials, acquittals or reversals on appeal, resulting in a roughly 87% conviction rate for no-body homicides nationwide.

“The major obstacles for a no-body case are the lack of the body means you do not have the following: the time of death, the manner of death and the place of death. Then, of course after proving that the victim is dead, you have to prove that the suspect did it,” DiBiase wrote in an email to the Wyoming Truth.

And as the Lynn Bush case shows, it can take years until the prosecutor has amassed enough evidence to convict.

Attorney Amber Beaverson understands why Gakwa’s family and the Gillette community are eager for a resolution to the case. Beaverson, 44, has been a licensed attorney for 13 years and has practiced public and private criminal defense for three years in Wyoming, most recently as staff attorney for Legal Aid Wyoming in Gillette. She also teaches a criminal justice course at Gillette College, where Gakwa was a nursing student.

Beaverson remembers the outcry from faculty and students when Gakwa disappeared. It’s instinctual to want answers when a person goes missing or is believed to be a victim of a crime, she said.

“People want to know what happened. That’s the thing,” Beaverson said. “It’s like we’re spectators, in a way, and we want to feel safe and better about this anomaly of human behavior occurring.”

Gakwa’s family is no exception. On the one-year anniversary of her disappearance, they hand delivered a change.org petition to Gov. Mark Gordon, Gillette police and city council calling for concerted efforts to make her whereabouts known and seek justice for any potential crimes against her.

Beaverson said she has confidence in local police and the county attorney’s office. And she defended their need to keep a tight lid on any investigation, noting that without a body, it’s difficult for prosecutors to meet the burden of proof in a criminal case, and in this scenario, a confession often is the only evidence of criminal intent.

“The autopsy determines manner and cause of death and tells a huge part of the story,” Beaverson said. “There’s definitely a possibility that you could build a case from something like the blood evidence and what people saw or heard. But it’s still not the story that the body would tell you.”