Unpacking Snowpack: New Study Aims to Better Understand Links Between Forests and Water

Could strategic tree-thinning methods help offset demand in an increasingly thirsty West?

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Sep 17, 2023

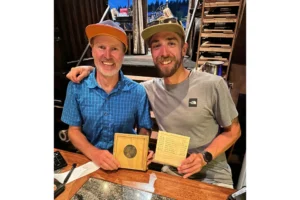

Carli Kierstead (right) and her team take a break while installing one of two snowtography stations in the Sierra Madre mountain range. (Photo credit, Jenifer Lamb. Courtesy of Carli Kierstead)

By Bob Wooley

Special to the Wyoming Truth

Water.

There may not be a more perplexing, confounding, important topic in the American West.

In Wyoming, issues around water don’t seem as urgent as they are in Arizona or California. But Western states and the water they share are connected in a very real way. And a new study by The Nature Conservancy (TNC), in partnership with the University of Wyoming and the U.S. Forest Service, could aid in understanding how to keep more water flowing into and through the Colorado River to the benefit of millions of residents.

At the center of the study is snowfall. Carli Kierstead, TNC’s lead researcher on the project, said there’s a dynamic interaction — like a dance — between the trees in the forest and the snow falling from the sky.

“The better we can understand that dance, the better we can optimize the ways we thin our forests,” said Kierstead, a Yale-trained environmental management, water and landscape scale conservation expert.

How the study works

When snow falls onto dense forest canopy, trees often prevent it from hitting the ground. That snow is then more likely to melt and evaporate without adding to the ground water.

The study is aimed at figuring out how different forest structures and different arrangements of forest thinning can provide the right amount of shade in some places and the right amount of openings in others.

Kierstead said the research project will use a method called snowtography to measure the effects of forest thinning. It will allow researchers to understand if and how proactive forest thinning strategies that are already taking place in the state can help improve water levels in Wyoming and help communities that rely on snowpack for water.

“One of the ways I like to describe this whole dynamic between forests and water is to talk about them as our natural water towers,” she said. “They’re this free infrastructure that we have in the mountains, where we have all of this water supply that’s held in our forests in the form of winter snowpack.”

Over five days in July, Kierstead, along with 25 students and researchers, installed two research stations on the western slope of the Sierra Madre mountain range. The stations are part of a larger network of snowtography research sites spanning the Colorado River Basin. The Wyoming sites – the first installed near the top of the basin – were located near the headwaters of the Colorado River in areas where the forest had recently been thinned to measure and monitor the effects of the thinning on snowpack and soil moisture. The other sites are in Colorado and Arizona.

At its most basic, snowtography is a snow monitoring system where automated cameras are installed in trees and aimed at snow stakes that are placed in a straight line across the landscape. This is called a transect, Kierstead said. The cameras, over the course of a snowy winter season, capture photos of the snow depths in forest areas that have been thinned and those that have not been thinned. The snow stakes are marked with depth measurements sort of like a yardstick.

A second part of the research involves digging one-meter deep pits in the ground and burying moisture sensors at different depths to better understand moisture levels and how the water moves through the land. The equipment, supplies and monitoring capacity used in the research are paid for through a mix of private and public funding, Kierstead said.

Snow boots on the ground

While the technology the stations utilize is relatively low cost and not very complicated, the remote locations of the test sites present a challenge.

“In an ideal world, you would have cell service in these areas and the cameras can just send you all of the pictures they’re taking,” Kierstead said. “Unfortunately, we do not have cell service in the study area. So, we’re going to be relying on our partnership with the University of Wyoming.”

UW undergraduate students will collect data from the test sites once an appropriate amount of snow accumulation occurs this fall. They also will take snow density measurements in person.

Despite heavy amounts of precipitation in 2023, there have been multiple drought designations for Wyoming counties as recently as 2022. And since more water in already arid climates is generally preferable to less, figuring out how to retain water from snowfall is knowledge that can provide dividends in the future.

“[The research is] going to be really meaningful for local folks in Wyoming to have a better understanding of the water that gets down to our communities,” Kierstead said.

The research could also be of benefit because to put it bluntly, Wyoming is dry. In fact, it’s generally one of the top five or six driest states in the country behind Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico and Utah.

The state gets around 70% of its water from snow. And Cheyenne, where just shy of one-in-nine Wyoming residents hang their respective hats, gets around 70% of its water (in a pretty confusing, roundabout way) from the upper Colorado River Basin.

As one of seven states that make up the Colorado River Compact of 1922, Wyoming is entitled to a certain percentage of the Colorado River’s water. The actual amount is 14% per the Upper Basin Compact ratified in 1948. Wyoming uses its water from the river for a vast array of purposes, including water supply, recreation and fish and wildlife habitat.

It’s no secret that the Colorado River is drying up. It has been for a while. But to put it in even more grim perspective, scientists from the UCLA Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences recently released a report they claim shows that climate change has basically robbed 10 trillion gallons of water from the Colorado River Basin between 2000 and 2021. At the same time, populations in cities across the West have grown, creating more demand.

Because of yearly variations, the snowpack study will last for a minimum of three winters before any trends can be gleaned from the data. But at the three-year mark, researchers can use that information in scientific models to not only help with understanding, but also predict future patterns, Kierstead said. The cameras also allow researchers to expand the scope of the study if the team decides it wants to look at biodiversity or a wildlife component.

“The study plays an important role in TNC’s larger goal of advancing scientific understanding of where and how ecological forest thinning can help society adapt to a changing climate,” Kierstead said.