The Looming Revival of Wyoming’s Uranium Mining for Nuclear Power

As the US seeks more domestically produced nuclear fuel, Wyoming’s formerly dormant uranium mines may start back up

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Nov 02, 2022

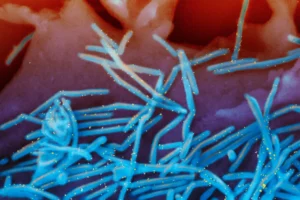

Some mined uranium becomes “yellowcake,” a solid powder form of processed uranium oxide that has to be further altered before it can be used in a nuclear power plant. (Courtesy photo from Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Energy Fuels Inc.)

By Sarah Scoles

Special to the Wyoming Truth

Out with the old, in with the new-again: That’s the idea behind a new nuclear power project based in Kemmerer. A next-generation nuclear reactor, dubbed Natrium, will be built in the town by 2028—on the (soon-to-be-former) site of the to-be-closed Naughton coal power plant. The effort is a joint venture between the Department of Energy and a company called TerraPower, backed by Bill Gates.

But the status of U.S. nuclear power—in the TerraPower project, in the Cowboy State more broadly and beyond—depends on more than big names, big money and big dreams. It also depends on uranium—and in Natrium’s case, a processed variety of uranium called HALEU, or high-assay low-enriched uranium. Increasingly, both energy companies and policymakers are interested in revamping the domestic supply of the radioactive stuff, which will require revamping the uranium mining industry.

That means Wyoming could experience a resurgence of this particular kind of extraction, alongside a surge in alternative energy sources. The state creates 13 times more energy than it consumes—and much of its power in the power sector has historically come from coal. That fossil fuel, though, is on its way out, its power production predicted to decline by nearly half by 2030.

“Nuclear power is a good bridge to try and maybe not completely remove coal, but to help in that transition,” said Pedro Mena, a researcher at Idaho State University who recently published a study on American West markets for atomic energy. If Wyoming chooses to go nuclear, he continued, “they can maintain their status as an energy producer.”

Right now, much of the uranium for nuclear power comes from outside the United States. In 2021, the owners and operators of U.S. nuclear power plants bought 46.74 million pounds of uranium from other countries—the largest of which are Kazakhstan, Canada, Australia and Russia. Just 5% of it came from the U.S. As a result of that foreign dependence, the country’s uranium mines—many of which are in Wyoming, home to the largest known deposits in the country—have gone eerily quiet in recent years.

But things have started to change, because of a desire for domestic self-sufficiency and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Nuclear operators are, once again, turning their heads home.

“We have seen a marked uptick in interest from domestic nuclear utilities, seeking to diversify their suppliers of uranium away from Russia in particular,” said Curtis Moore, a vice president at Energy Fuels, which owns uranium facilities in Wyoming.

One of those (future) nuclear utilities is TerraPower. While the company declined to speak for this story, its website states that it is committed to supporting a domestic HALEU supply.

And so with TerraPower and other nuclear projects seeking homegrown fuel, uranium mines in Wyoming are likely to spool up.

Cold war, hot material

Uranium mining was once big business. It hit its boom during the Cold War, when the U.S. needed a huge supply of the radioactive stuff to make more nuclear weapons and nuclear power. By the early 1980s, that wave was cresting. But then nuclear power-plant construction slowed, and the country started to snap up more of the element from abroad.

“The Russians were offloading very cheap uranium,” said Bruce Thomson, emeritus professor at the University of Mexico and the author of a 2021 report about environmental contamination from uranium mining and processing.

“The price of uranium plummeted,” he continued. When a commodity’s value dips, the sales money a company gets doesn’t always justify the cost of mining the material.

In 1985, for the first time since 1961, the amount of uranium the U.S. imported surpassed what it produced, and those statistics have stayed fairly flipped. But with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and general international instability, the U.S. is seeking more motherland mineral supplies.

“We’re undergoing a period of deglobalization right now,” said Moore. “I think that as a nation we’re coming to the realization that there are some capabilities that are just too important to sell off to the lowest bidder.”

Should that realization result in a new domestic mining boom, it will include Wyoming. The Powder River Basin and the Great Divide Basin are potential hotbeds of activity. And the state is already home to facilities like Cameco’s Smith Ranch-Highland operation and Strata Energy’s Lance Projects (Cameco declined to comment, and Strata did not respond to a request for comment). Many of the existing mining operations, including Cameco’s, have been put on hold until the cost-benefit equation makes more sense.

Energy Fuels—and its many Wyoming-uranium sites—is ready for that balance to tip. The company’s main facility is called Nichols Ranch, located near Linch in central Wyoming. Its production was paused in 2018, but the company is prepared to take it off standby and into glowingly greenlit territory, said Moore.

Ur-Energy, another uranium producer, has two big Wyoming facilities: Lost Creek and Shirley Basin. Should the money make sense, ramping things back up at Lost Creek, where infrastructure already exists, will take about six months. Shirley Basin has its paperwork in order but will require construction.

In other places, like New Mexico, uranium is stashed closer to population centers and Native land, so its extraction elicits more concern.

“The mines in Wyoming are really remote,” said Thomson. “They’re out in the middle of nowhere. And you don’t have much public opposition that I’m aware of.”

Radioactive risks

Still, public opposition is understandable. Uranium mining, after all, has historically resulted in environmental degradation and health problems.

“There were virtually no regulations at the time to protect the environment or the health of the miners themselves,” said Thomson, of the Cold-War era.

Uranium mining, in the past, happened more in open pit and subterranean operations, which left workers breathing in cancer-causing radon and left waste sitting around to blow in the wind and seep into the groundwater. “It really wasn’t until the ‘90s people started becoming real concerned about some of these things,” said Thomson.

Still, the legacy impacts remain. Wyoming currently has seven former “uranium recovery sites” undergoing reclamation and remediation.

Today, uranium mining tends to use less poisonous processes and subjects workers to fewer health risks. The method of mining used in all Wyoming uranium facilities doesn’t happen underground and produce piles of waste. It’s a process called “in situ recovery mining,” which involves circulating a water solution into the ore and dissolving the uranium, which can then be chemically separated.

“The environmental threats are and the risk to the miners almost nonexistent,” said Thomson.

Those procedural changes have helped with public acceptance, which has also increased because a stateside uranium supply is in the service of nuclear power—a cleaner and more efficient energy source than fossil fuels. “Even some of the environmental groups are now supporting nuclear power, because it’s carbon-free,” said Thomson.

The mining itself, though, isn’t quite zero-emission, nor is the construction of a plant like TerraPower’s. The safety and hazard record of in situ mines, including some in Wyoming, isn’t impeccable. The reactor industry isn’t free of accidents or regulatory violations, either.

Nuclear power and its supply chain are neither 100 percent safe nor 100 percent green. But Wyoming, said Mena, is well positioned to play a part in the industry from its start (mining) to the finish (pumping out electricity).

“There’s a lot of opportunity to have logistical savings, just in having the source of the fuel close by,” said Mena.

Regardless of whether TerraPower’s project succeeds, or more atomic-energy plants are constructed in Wyoming, the state’s uranium will likely fuel other regions’ reactors.

“If the public will accept nuclear power,” said Thomson, “I think there will be more uranium mines.”

Sarah Scoles received a grant from the International Women’s Media Foundation’s Howard G. Buffett Fund for Women Journalists to support the book she is writing about nuclear-weapons scientists.