Wyoming’s Judiciary Seeks More Staff and Funding For ‘New Normal’

Branch’s proposed budget up over 30% from the last biennium

- Published In: Politics

- Last Updated: Dec 19, 2023

A statue of Justice Willis Van Devanter, the first Wyomingite to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court, is seen outside the Wyoming Supreme Court. The state court is requesting a significant budget increase to deal with a changing landscape. (Wyoming Truth photo by CJ Baker)

By CJ Baker

Special to the Wyoming Truth

Facing more complex and contentious cases, leaders of Wyoming’s court system are calling for more funding and staff.

“We didn’t necessarily sign up to do social work,” Wyoming Supreme Court Chief Justice Kate Fox told the Legislature’s Joint Appropriations Committee last week. “But the truth is that the people in our courts and in the judicial system need a different kind of support than we have traditionally provided.”

Among other challenges, judges are seeing an increasing number of defendants with issues related to mental illnesses and substance abuse, Fox said, which has pushed the court’s role beyond legal analysis.

“Our traditional approach of finding a person guilty of a criminal offense, locking them up and then turning them loose with exactly the same mental illness — or maybe a worse one — doesn’t work,” she said.

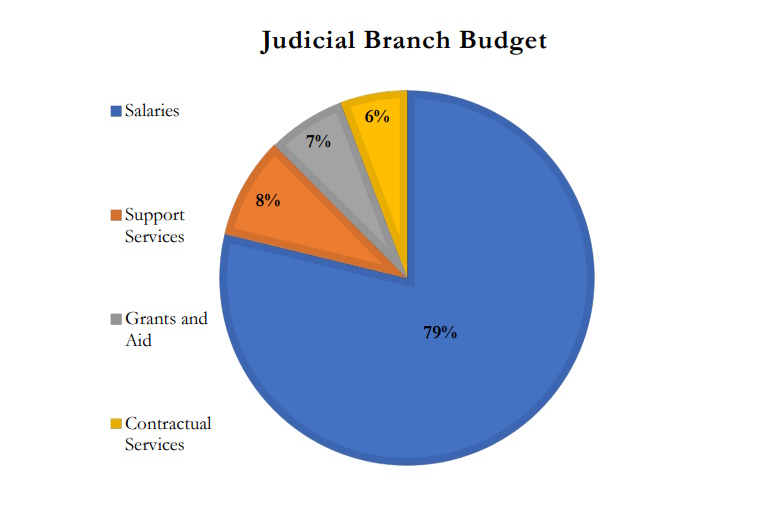

The chief justice made the comments as she presented the judiciary’s roughly $121 million budget proposal for the 2025-2026 biennium. Her plan includes new efforts to keep mentally ill people who commit low-level crimes out of jail and in treatment, aid self-represented litigants and support overburdened court staff.

The proposal represents a significant increase from the $92 million budget put forward two years ago. Some of that jump stems from the roughly 16% raises state employees received over the past biennium, and from the judiciary taking over the state’s treatment courts. But the proposal also seeks to add 19 more positions and provide another bump in wages for many of the 342 people already working in the judiciary.

Fox suggested lawmakers might see the courts as “just a growing bureaucracy,” but she said it’s “a critical branch of government that is playing catch-up after a century or two of doing things the same way we did at statehood.”

Managing mental health

At first glance, the state’s courts might not seem busier.

In fiscal year 2023 that ended in June, the state’s district courts — which oversee divorces, child custody disputes and the most serious criminal and civil cases — handled 13,386 cases, down 3% from the prior year.

The circuit courts, meanwhile, handled 91,534 matters, representing a 7% drop from fiscal year 2022. Traffic citations represent the bulk of the lower court’s cases and fell 11%, perhaps in part to a staffing shortage that’s left fewer troopers patrolling Wyoming’s highways.

Over the past five years, cases declined about 30% in the district courts and 40% in circuit courts, while the Wyoming Supreme Court’s docket has remained fairly steady.

Fox noted “filings have not increased,” but said the time needed to manage each case has “multiplied.” State Courts Administrator Elisa Butler said they’ve heard fewer parties are settling and compromising, with more trials, appeals and bond/probation revocations.

Alongside the state’s “mental health crisis,” Butler said judges and staff are also dealing with a “deluge” of self-represented litigants who take up more time, increased demands for better technology and instant access to information, all within “a more litigious and polarized society.” It is, she said, the court system’s “new normal.”

The budget proposal is a recognition the judiciary “must mature and adapt,” Butler said. For example, the officials are seeing low-level offenders go in and out of jail while their mental health or substance abuse issues go unaddressed. The “revolving door” is expensive, burdensome and “gets the poorest possible results,” Fox said.

An upcoming experiment in Gillette seeks to get those folks into treatment, being launched with existing court staff and cooperators from other agencies. However, if the project expands across the state, Butler said the judiciary will need a new behavioral health services manager to coordinate the effort; the person would also oversee the state’s treatment courts after the program is transferred from the Department of Health to the judicial branch in July.

Joint Appropriations Committee Co-Chair Sen. Tara Nethercott (R-Cheyenne) said the new manager could save the state money — particularly if they can improve the process for involuntarily committing those experiencing a mental health crisis. So-called Title 25 proceedings are “a huge financial expense,” Nethercott said, because “it’s not administered effectively or efficiently and is so convoluted.”

Boosting staff

Separately, Fox is proposing a new way to assist those who represent themselves in court.

The judiciary already provides self-help forms and online resources through Equal Justice Wyoming, but a planned program in Natrona County will provide volunteers who can tell pro se litigants which paperwork to fill out, what to expect in court and ultimately get a result, Butler said. The hope is to help participants better understand the system while freeing up time for judges and court staff.

The judiciary is seeking to hire a court navigator administrator to oversee the pilot program and any future expansions, along with a grant writer to land and manage high dollar grants for future innovations.

They’re among 10 positions Fox wants to add to the Administrative Office of the Courts, at a cost of nearly $2.5 million. It’s a significant scale up from the 38 or so current employees, who the justice said have too many tasks.

“Highly skilled people are taking out the trash,” Fox said, “and that doesn’t make a lot of sense.”

She also wants to boost the circuit courts, requesting $1.5 million to add nine more clerks to the busiest areas.

The biggest so-called exception request is an additional $5.4 million for salary increases. Although the state’s recent raises helped, Butler said employees in the judiciary earn about 10% less than their counterparts in the executive branch.

Another $24,000 would provide mental and other wellbeing health services to judicial employees, who Butler noted can “see terrible things.” The proposal also calls for $75,000 to allow the state’s 55 judges to take needed time off — they are “becoming exhausted,” she said — and $24,000 to scrub their personal information from the internet in the face of “ever more important” security concerns.

Other exception requests include increased IT costs ($1.5 million) and a need for more interpreters to assist the growing number of non-English speakers in the courtroom ($47,000).

Lawmakers posed various questions during the Dec. 13 hearing — wondering, for example, if the judiciary’s comparison to executive branch salaries was “apples to apples” and whether the transition to electronic filings will lessen the need for additional clerks.

Sen. Dave Kinskey (R-Sheridan) said he wasn’t sure he could back the entirety of the “bold” budget request, but praised Fox for “pulling people together to really achieve, I believe, a transformation in the administration of justice in Wyoming.” Kinskey said it’s needed, since the U.S. prison system is “the largest provider of social services in the United States.”

“It’s a big ask, but it’s a big job, and you’ve taken it on,” he told Fox, “and … it’s kind of hard to ask somebody to take on the job and then deny them the resources to do it properly.”

The appropriations committee will “mark up” the judiciary’s request and Gov. Mark Gordon’s $9.95 billion proposal for the executive branch in the coming weeks, presenting its recommendations to the full Legislature in February.