Liz Cheney’s Crusade: Personal or Constitutional?

The Wyoming rep. must overcome an intense battle to retain her seat but some wonder if she’s set her sights on something bigger

- Published In: Politics

- Last Updated: Jul 05, 2022

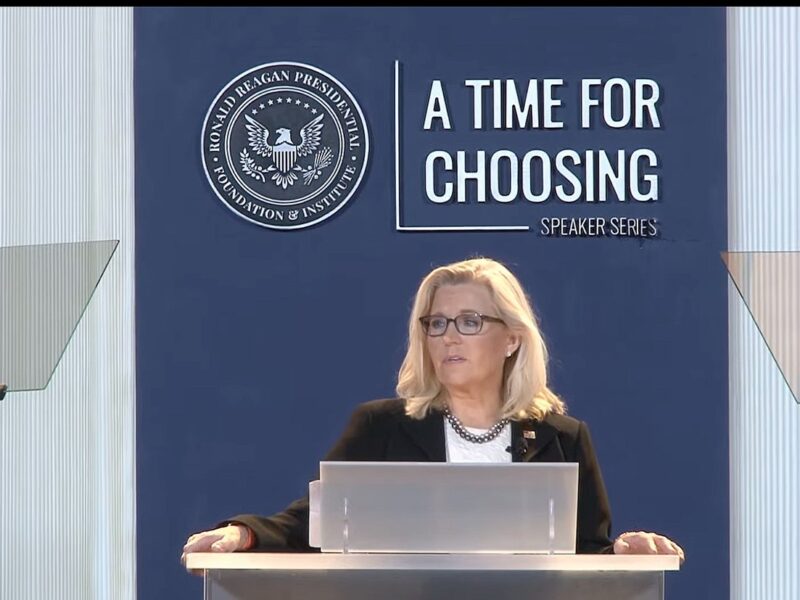

“Republicans cannot both be loyal to Donald Trump and loyal to the Constitution,” says Rep. Liz Cheney (R-Wyo.) at a speech at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library in California on June 29, 2022. (Wyoming Truth photo courtesy of Ronald Reagan Presidential Library’s speaker series)

By Jacob Gardenswartz

Special to the Wyoming Truth

It was a Wednesday in late June, and Liz Cheney was in California.

The morning before, the Wyoming Republican member of Congress was in Washington, D.C. There, in her role as vice chair of the House select committee investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection, she presided over a surprise blockbuster hearing which revealed that former President Donald Trump had allegedly endorsed the idea of his supporters bringing weapons to his speech ahead of the riot at the U.S. Capitol, noting that the rally-goers were “not here to hurt me.”

The evening after, Cheney would be in Sheridan, Wyoming. There, she’d debate her four GOP challengers in the Aug. 16 primary for Wyoming’s sole House seat, which she’s held since 2017. Cheney’s top rival, attorney Harriet Hageman — who, with Trump’s backing, represents the most significant electoral threat Cheney has faced since she was elected to Congress — worked to paint Cheney as out of touch with voters, claiming that Wyomingites “do not believe that they’re being represented in Congress right now because our representative doesn’t come to Wyoming.”

So it was curious, then, that two days before early voting was set to begin for her make-or-break election, Cheney was in arid Simi Valley in southern California, some 1,200 miles away from the debate stage. She was there to deliver a speech at the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library as a part of the “Time for Choosing” speaker series, described as a forum for “leading voices in the conservative movement to address critical questions facing the future of the Republican Party,” according to the organizer’s website.

Named for Reagan’s 1964 speech that launched the actor-turned-politician into national prominence, the series’ recent speakers have included Gov. Kristi Noem (R-S.D.), former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, former Ambassador to the United Nations Nikki Haley and former Vice President Mike Pence, among other potential 2024 presidential candidates.

In introductory remarks on Wednesday, Reagan Institute Director Roger Zakheim drew immediate parallels between Reagan and Cheney, recalling Reagan’s decision to challenge President Gerald Ford at the 1976 GOP convention. “When he felt that conservative principles were at stake, Ronald Reagan did not hold his tongue,” Zakheim said. “He did what he believed was best for the party and the country, even if it meant bucking party leadership or a sitting president.”

Cheney, in her remarks, which touched on everything from her pro-democracy work abroad to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to the Biden administration’s energy policy, seemed to embraced the Reagan analogies. She pulled no punches in her evisceration of GOP leadership who, she said, “made themselves willing hostages to this dangerous and irrational man,” Donald Trump.

Cheney’s blunt proclamation mid-speech that “Republicans cannot both be loyal to Donald Trump and loyal to the Constitution” received raucous applause, as the audience of Democrats, establishment GOP operatives and disaffected Republicans celebrated what they saw as a principled stand against demagoguery.

Despite the many Reagan comparisons, Cheney appeared to be what some might describe as Clintonesque. In tone and tenor, Cheney exudes a decidedly Hillary Clinton flair: she speaks slowly and with clarity, her voice pitched low and her diction crisp. Indeed, as she continues to beat the drum against Trump — much to the chagrin of many Wyoming voters — perhaps Cheney has set her sights on that glass ceiling Clinton failed to break.

“Let me also say this to the little girls and to the young women who are watching tonight,” Cheney said towards the end of her speech in California. “These days, for the most part, men are running the world. And it is really not going that well.”

From carpetbagger to conservative stalwart

Elizabeth Lynne Cheney’s first foray into electoral politics didn’t go well, either.

In July 2013, she made the surprising announcement that she’d challenge Wyoming’s incumbent Republican Sen. Mike Enzi for the GOP nomination, arguing in her campaign launch video that the state needed “a new generation of leaders to step up to the plate.”

There was no denying that the Cheney brand was popular in Wyoming. Dick Cheney, Liz’s father, had represented Wyoming in the House of Representatives for six terms before going on to serve as vice president under George W. Bush.

Liz Cheney was born in Madison, Wisconsin, and though she spent part of her childhood in the Cowboy State while her father was running for Congress, she’d graduated from McLean High School in the D.C. suburbs. Her resume is not too dissimilar from those of other politicos’ children — early career jobs in international affairs, a law degree from the prestigious University of Chicago and some later posts in the State Department, on political campaigns and with conservative media.

All that’s to say, the Cheney name alone and Washington connections couldn’t propel her to victory in that first Senate bid. The National Republican Senatorial Committee continued to support Enzi, as was its policy. Cheney was accused of carpetbagging and fined after applying for a Wyoming fishing license without meeting residency requirements. Reporter Jon Ward observed in The New Republic that at one campaign event, Cheney’s “jeans were so new that her hands were stained blue from touching them.”

In January of 2014, less than six months after she’d announced her candidacy, Cheney dropped out of the race, citing family health issues.

Cheney’s subsequent bid for Wyoming’s House seat went more smoothly. Incumbent Rep. Cynthia Lummis, who now represents the state in the Senate, had announced her retirement in 2015, and Cheney was considered the front-runner to replace her from the moment she entered the race. She captured the GOP primary by a 17-point margin and won the general election with nearly two-thirds of the vote.

Shortly after she was reelected in 2018, Cheney’s GOP colleagues voted her chair of the House Republican Conference, making her the third-ranking Republican in leadership despite only having served fewer than two years in Congress. In 2020, she won reelection with an even greater share of the vote, almost 70 percent, prompting much speculation about whether she’d seek a Senate seat or even the Speaker’s gavel.

While in Congress, Cheney earned a reputation as a solid conservative, known for her hardline positions against environmental regulation (she opposes Endangered Species Act protections for grey wolves and grizzly bears), hawkish foreign policy views (she supports waterboarding) and opposition to same-sex marriage (a position which led to a public falling-out with her sister Mary, who is married to a woman; Cheney has since said she was “wrong” to oppose her sister’s union).

For the most part, Cheney was a staunch supporter of Trump. She voted with his positions 93 percent of the time, according to an analysis by FiveThirtyEight, and frequently took to cable news to defend him amid controversies.

During special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into possible links between Trump and the Russian government, Cheney said statements by FBI agents investigating him “could well be treason.” She argued Democrats’ first impeachment of Trump for his conduct with regard to Ukrainian foreign aid was partly responsible for Turkey’s invasion of Syria (a claim Democratic House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s spokesman called “delusional”). The New York Times noted in late 2019 that Cheney and Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.), one of the most conservative politicians in Washington, were “warring” over “who’s Trumpier.”

What then explains Cheney’s transformation? How did a woman who defended Trump amid hot-mic comments about groping women during his 2016 campaign go on to become his foremost Republican critic?

To some, Cheney’s shift represents a principled stand on behalf of democracy and the Constitution. To others, it’s the calculated and opportunistic posturing of someone with great political ambitions.

There is no doubt, though, that Cheney’s primary fight impacts more than just the political representation of the nation’s least-populated state. It’s about the future of the Republican Party, of Donald Trump and, according to Cheney, our constitutional republic.

Liz Cheney, a ‘lodestar’ for democracy

Like a Wyoming thunderstorm, Liz Cheney’s pivot on Trump came almost in an instant.

She was not the first prominent supporter to denounce the ex-president. Before her came, among others, his former chief of staff Mick Mulvaney.

There were a few early warning signs. Despite her steadfast support of most of Trump’s policies, Cheney had vocally pushed back against the White House on issues of foreign affairs, rejecting Trump’s “America First” doctrine as isolationist and “wrong.”

Then came Covid. As the former president promised the nation the virus would “disappear,” Cheney advocated for pandemic precautions like wearing masks. While Trump attacked Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Cheney defended him as “one of the finest public servants we have ever had,” earning her a pile-on from some of Trump’s congressional allies.

But it was Trump’s rhetoric leading up to, during and after the 2020 election that pushed Cheney over the edge.

On Jan. 3, three days before the Capitol attack, Cheney distributed a 21-page memo to her Republican colleagues refuting Trump’s unsubstantiated claims to victory in six states. Those efforts worked to focus Trump’s ire on Cheney. In his Jan. 6 speech just outside the White House, Trump told his supporters, “We got to get rid of the weak congresspeople, the ones that aren’t any good, the Liz Cheneys of the world.”

Many of them tried. As the Capitol was being ransacked, Cheney and other lawmakers were rushed to a secure room. She soon phoned into the president’s favorite network, Fox News.

“There is no question that the president formed the mob,” Cheney said. “The president incited the mob, the president addressed the mob.”

But many Republicans who publicly broke with Trump on Jan. 6 soon found their way back to him.

Not Cheney. She has continued to speak out against the 45th president in public and in private, joining nine other Republicans to vote for his second impeachment and accepting Pelosi’s invitation to serve on the committee investigating Jan. 6, one of just two GOP members to do so.

In response, the Wyoming Republican Party voted to censure Cheney, calling on her to “immediately resign.” In Congress, her GOP colleagues ousted her from her leadership post. And the Republican National Committee also has censured her, arguing she and fellow Jan. 6 committee member Rep. Adam Kinzinger (R-Ill.) “support Democrat efforts to destroy President Trump more than they support winning back a Republican majority in 2022.”

“She’s not somebody who’s been lying in the bushes, waiting for Trump to make a mistake,” said David Eisenhower, grandson of the 34th president and a historian of presidential rhetoric at the University of Pennsylvania.

“I think she was moved in a particular way by January 6, and so that puts her in a different category,” Eisenhower added. “The Congress is a special place. It’s like the World Trade Centers. It’s a sort of sanctuary. It’s a sacred place that was violated, and I think that gives this entire process a strange coloration.”

As Republicans turned on Cheney, her Democratic colleagues stepped in with praise. “Let us salute Liz Cheney for her courage,” Pelosi has said.

But their lionization comes with a cost. The more Democrats talk up Cheney, the less Republicans in Wyoming seem to support her.

“She is the lodestar here,” Eisenhower said. “The meaning of January 6 comes down to her. If she is violated for it, I think that it has not made an impression. If she finds a way to survive as a voice or whatever, I think that this thing has made a great impression.”

Cheney: presidential aspirant?

Donald Trump won Wyoming in 2020 by more than 43 percent— a greater margin than he did any other state in the country.

The former president remains immensely popular. When he flew in to rally for Hageman in May, he amassed a crowd of thousands.

“Liz Cheney hates the voters of the Republican Party, and she has longer than you would know,” Trump said during his speech. “Our greatest danger is not from outside of our country. Our greatest danger is these sick people from within.”

Trump’s appeals seem to be working.

“Everyone I know is voting for Hageman,” said Michael Summers, a former Marine who now works as a substitute teacher in Gillette.

Will Collier, a real estate agent and former coal miner in the same community, is no fan of Cheney but wishes Trump had latched on to a different wagon. He likes Chuck Gray, a state legislator who was running for Cheney’s seat but dropped out when Trump endorsed Hageman.

Collier said Cheney’s leadership of the Jan. 6 investigation “just proved what we already felt about her,” that she never really was “for Wyoming.” And yet, he said, “I find it hard to believe that Liz Cheney is going to lose.”

Only two polls of the primary race have been publicly released to date, each sponsored by groups supporting Hageman. Both found her leading Cheney by around 30 percent. Though Cheney has a strong fundraising edge — raising $3 million in the first quarter of 2022, more than double that of Hageman’s $1.3 million in the same period — much of those donations have come from out of state.

Ads have painted Cheney as more loyal to Democrats than she is to Wyoming Republicans, with one tying her to Hillary Clinton: “She benefited from a famous political last name. She sided with Nancy Pelosi and attacked President Trump when he was in office. She supported impeachment and she continues to attack President Trump today,” the narrator says ominously.

“Hillary Clinton? No, Liz Cheney.”

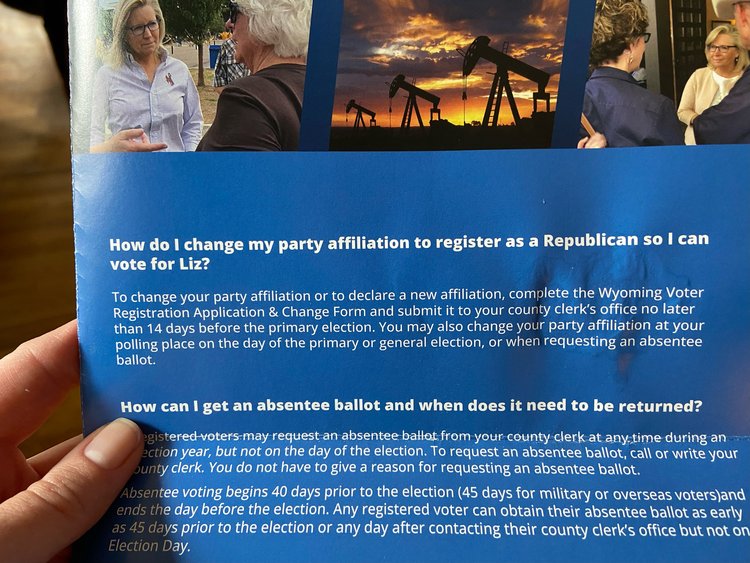

In an apparent acknowledgement of her struggles with GOP voters, the Cheney campaign has reached out to registered Democrats in the state, sending them information on how to switch their party registration and support her in the primary. (Representatives for Cheney’s congressional office and her campaign declined to comment on her approach to the race, outreach to Democrats or ongoing criticism of Trump.)

Kennedy Penn-O’Toole, a librarian and political science lecturer at the University of Wyoming, is one such Democrat who received the mailer and intends to re-register to vote for Cheney.

“I disagree with her in, you know, 90 percent of cases, but I really respect what she’s done with the January 6 committee work,” Penn-O’Toole said. “I feel like she’s been brave and that she is looking at the larger picture of the state our democracy’s in.”

But even if every Democrat in the state were to cross-over and support her, Cheney still wouldn’t be out of the woods. The state is vastly Republican; she has to improve her numbers with GOP voters to be competitive.

That’s why some wonder whether retaining her seat is really Cheney’s long-term goal.

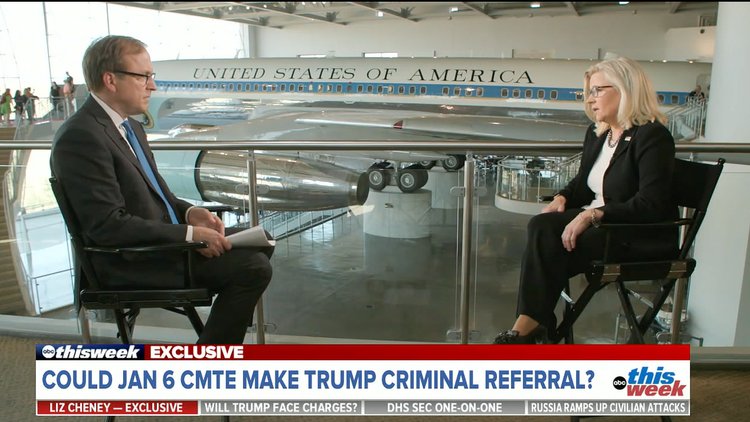

Amid the media spotlight from her Jan. 6 work, Cheney has been floated as a possible 2024 presidential candidate by pundits and political commentators. She’s been asked several times about possible White House aspirations, most recently in an ABC interview on Sunday.

“I don’t intend to lose the Republican primary in Wyoming,” Cheney told ABC’s chief Washington correspondent Jon Karl.

Still, she said the GOP “can’t survive” if Trump, who’s been inching closer to another presidential run, is the nominee.

So, would she run for president herself?

“I haven’t made a decision about that yet,” Cheney said, noting she’ll figure that out “down the road.”

“But I think about it less in terms of a decision about running for office and more in terms of, you know, as an American and as somebody who’s in a position of public trust now, how do I make sure that I’m doing everything I can to do the right thing?” Cheney added. “To do what I know is right for the country and to protect our Constitution?

Back in Wyoming, some supporters are ready for a Cheney presidential run.

Dr. Joe McGinley, a radiologist who served as chair of the Natrona County Republican Party, is a long-time Cheney fan. He hopes she’ll win the upcoming primary to demonstrate that “there’s still a soul here in the Republican Party, and that there’s still people out there that are going to put principles in front of politics.”

But if Hageman or one of the other challengers prevails, “that’s not the end of the story,” McGinley said.

“I think she’s showing what true leadership looks like and will make an excellent president, and I hope she does consider that down the road,” McGinley said. I hope she does look for higher office.”