Feds Revise Regulations for Returning Native American Human Remains, Cultural Objects

Final rule gives tribes more authority

- Published In: Politics

- Last Updated: Dec 20, 2023

The Men’s Society of the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan carry boxes that hold the remains of over 100 ancestors and 200 associated funerary objects to the Nibokaan (Place of Sleeping) Cemetery for reburial during a ceremony. (Courtesy photo from Marcella Hadden, Niibing Giizis Photography via the National Park Service)

By Shen Wu Tan

Special to the Wyoming Truth

The Biden administration has approved a final rule amending procedural regulations for the return of Native American human remains and other culturally significant objects that gives more power to tribes.

The U.S. Department of Interior published the final rule of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) on Dec. 13, outlining revised policies for museums and federal agencies to identify and inventory Indigenous human remains and cultural items in their collections.

The rule, which takes effect on Jan. 12, bolsters the authority and role of tribes and Native Hawaiian Organizations (NHOs) in the repatriation process. It mandates that federal agencies and museums obtain free, informed consent from tribes, NHOs or lineal descendants before exhibiting, accessing or researching human remains or cultural objects.

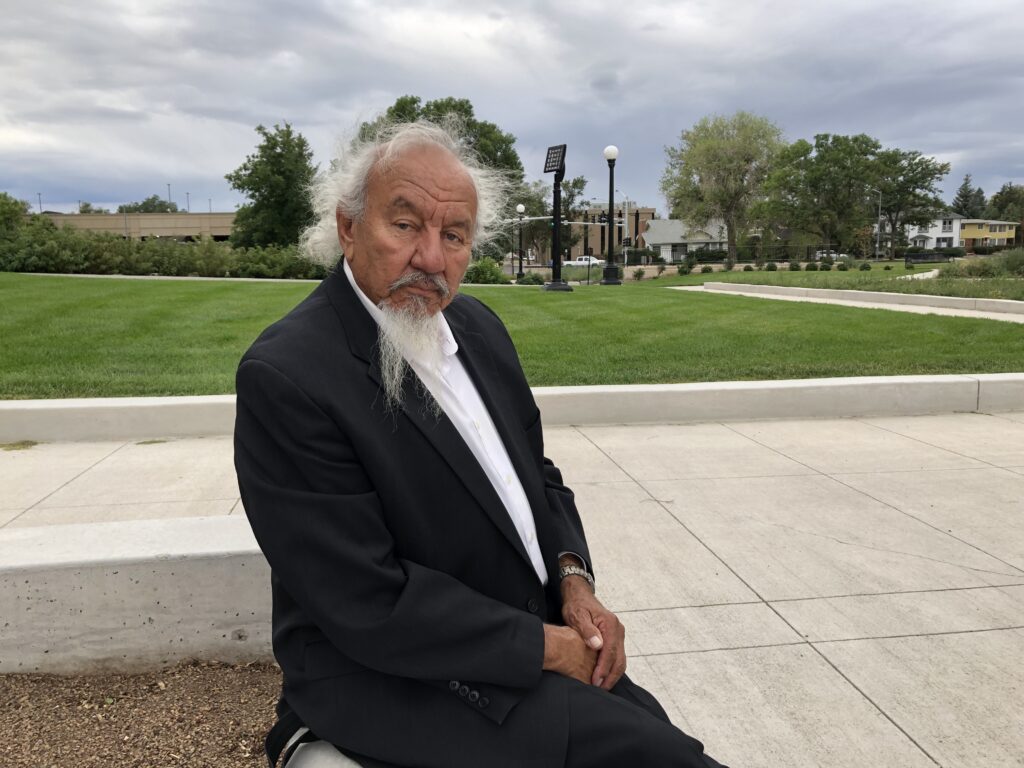

“This is one of those pieces where it takes the upper administrative muscle to say to states…to public institutions and individuals who know doggone well that they’ve had access to, and probably have within their homes or buildings, funerary objects, ceremonial objects, cultural items that they have no business with,” Sergio Maldonado Sr., a Northern Arapaho Tribe member, told the Wyoming Truth. “So, I like that notion of strengthening authority [of tribes].”

Additionally, the revised regulations eliminate the category of “culturally unidentifiable human remains” in the repatriation process. Many Native American human remains are indeed identifiable, so museums and federal agencies will have to reevaluate their decisions on cultural affiliations of these remains in consultation with tribes and NHOs, according to Melanie O’Brien, national NAGPRA program manager at the National Park Service.

Museums and federal agencies also will be required to update inventories of human remains and funerary objects within five years of the rule.

All federal agencies and entities with Native American collections that receive federal funds must comply with the revised regulations. Only the Smithsonian, which adheres to the National Museum of American Indian Act of 1989, is exempt.

“Comments from Indian tribes requested the regulations strengthen the authority and role of Indigenous communities in the repatriation process and empower tribes to protect what is sacred to them,” O’Brien told the Wyoming Truth. “The new NAGPRA final rule is the result of many months of nation-to-nation consultation.”

Native American human remains in the Cowboy State

NAGPRA, enacted in 1990, requires federal agencies and museums to identify Native American human remains, culturally significant items and funerary objects in their collections and to work with tribes and NHOs to repatriate them.

“These new rules are designed to improve the repatriation process and ensure transparency into museum and agency artifacts which may be covered by the NAGPRA law,” said Melissa Murphy, an anthropology professor at the University of Wyoming (UW). “We will continue to follow and obey these requirements to ensure NAGPRA’s goals of repatriation and return of remains and artifacts [are] met.”

The UW Human Remains Repository reported the removal of 54 Native American human remains from aboriginal land, according to a notice of a completed inventory published by the Federal Register in May.

Murphy said the remains are available for claims by any of the tribes listed in the notice.

A repatriation database from ProPublica reveals that institutions reported 75% of the more than 200 Native American human remains taken from Wyoming were made available for return to tribes. Twenty-one entities claimed to possess these types of remains from the Cowboy State, including the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody.

“The Buffalo Bill Center of the West is and always has been committed to both the letter and the spirit of NAGPRA,” said Rebecca West, the museum’s executive director and CEO. “. . . We work proactively with the federally recognized U.S. tribes and international Indigenous groups that are connected to our collections to not only ensure the return of their ancestors and heritage objects but [to] develop healthy collaborative relations with them.”

The center had three remains taken from Wyoming that were unavailable for return, per the repatriation database. It also states the museum has five remains from across the U.S. that were not made available for return, while two remains were made available.

Responding to the database’s findings, West noted many museums, including the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, are repositories for collections owned by outside entities; therefore, they do not hold legal titles for them and cannot act under NAGPRA.

“For the small amount of ancestral remains that the center has legal control over, these individuals have been reported and that information is available as part of the public record,” West said.

Last year, the Northern Arapaho government demanded the Peabody Museum at Harvard University return hair samples of Native Americans, including clippings from children who attended U.S. Indian boarding schools, from the 1930s.

The museum announced it was committed to returning the hair to families and tribal communities.

Although Maldonado applauded the federal government’s actions on NAGPRA, he wondered whether it was anything more than political words and asked: “How are you going to put the muscle into the authority of the tribes and NAGPRA?”