Following ‘Catastrophic’ Winter, State May Need To Relocate Deer

Researcher predicts it will take over a decade for populations to recover

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Aug 28, 2023

Mule deer in southwestern and south central Wyoming were decimated by the severe winter. As a result, some areas with good habitat may be completely devoid of deer. (Courtesy photo from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department)

By CJ Baker

Special to the Wyoming Truth

In the wake of a brutal and unprecedented winter, some of Wyoming’s mule deer and pronghorn populations are facing a long and uncertain path to recovery, with pockets of deer completely wiped out.

Some herds in southwest and south central Wyoming lost over 70% of their members to starvation, freezing temperatures and disease. The carnage was driven by heavy snowfall at low elevations that left few patches of open ground for wildlife to navigate and graze. The deep snow was compounded by the bitter cold, while stress made pronghorn more susceptible to a strain of pneumonia.

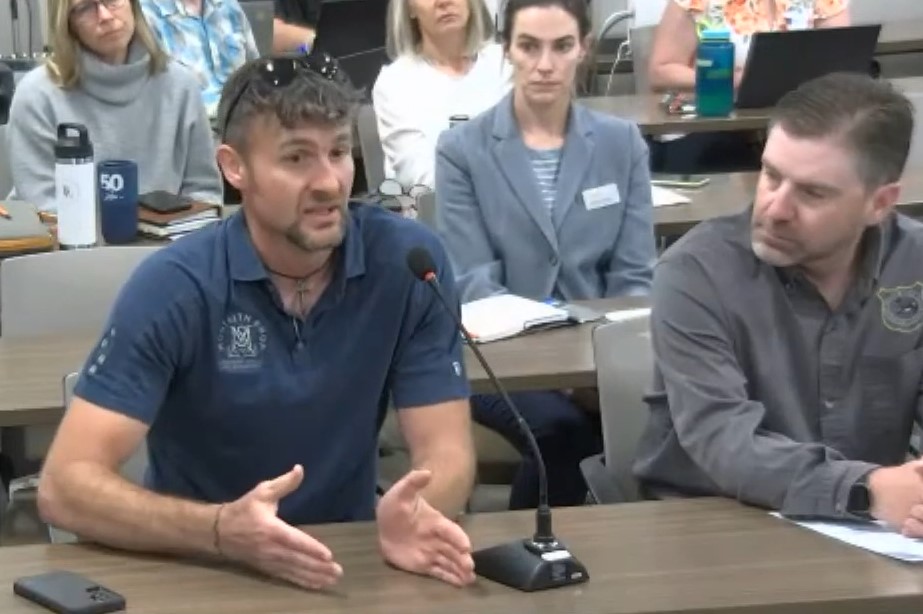

“There’s been lots of terms that have been floated around to describe it, ‘catastrophic’ certainly being one of them,” University of Wyoming ecology professor Kevin Monteith told the Legislature’s Select Natural Resource Funding Committee this month.

With so many animals dead, “there’s places on the summer range where we may have wonderful habitat, but there’s simply no deer occupying it anymore,” Monteith said.

The Wyoming Wildlife and Natural Resource Trust has historically focused on improving habitat, but it may need to be more proactive in boosting wildlife, said Executive Director Bob Budd. He mentioned the possibility of relocating mule deer from one area to another.

“If you think back 20 years ago, the issue was the habitat wasn’t sustaining the population,” Budd said. “Now we’re at a point where the habitat will sustain the population plus, but … we’ve got to figure out how to bump those animals into those areas.”

It might seem like a self-correcting problem, with deer simply moving into newly available habitat. However, Monteith’s research suggests that’s not the case.

Female deer typically make their summer homes right next to the range where they grew up, he said, and they rigidly stick to those areas. It results in a distribution that resembles a rose, with a matriarch deer in the center of the flower and its daughters forming the petals. But this winter likely wiped out entire families, Monteith said, leaving blank spots that won’t be filled anytime soon.

“It’s kind of like walling off portions of that summer range,” Monteith said. “It’s accessible to the deer, but they’re not using it because they’re such a faithful animal. They’re not going to go there just because the food is there.”

Given the severity of the losses, he said the impact will span multiple generations.

‘A whole different ball game’

Roughly 30% of the mule deer in the Wyoming Range succumbed to the winter of 2016-17, Monteith said. But this past year was on another level, killing 70% of the adult females, 65% of the males and pretty much all of the fawns, he said.

“Thirty [percent], you can sustain and probably replace in three years,” Budd said, “… but 70[%] is a whole different ball game.”

While the losses are “kind of hard to wrap your mind around,” Monteith said they could have been worse. The Wyoming Range deer entered last winter in relatively good condition, with 12% body fat. Had the animals been as skinny as they were heading into 2016-17, when the average body fat was around 8%, modeling suggests over 90% would have died.

“Meaning we would have almost lost everything,” Monteith said.

The conditions were so severe that it was “not energetically reasonable” for deer to paw through the snow, he said, limiting them to the sagebrush and other plants that poked through the surface.

“Better, taller, more robust sagebrush, again, is that food source that helps them persist through the winter,” Montieth said.

The state has worked to conserve its “sagebrush sea” as part of efforts to protect sage grouse and it’s also moved to protect migration corridors and install more wildlife-friendly fencing and road crossings.

Fencing is “a lurking thing” that affects wildlife, Monteith said, but its exact impact is hard to measure and it varies by location. For example, he said fences aren’t much of an issue for the muleys wintering in the Wyoming Range. Last winter also piled snow up to the top wire of some fences, which effectively made the type irrelevant, Budd indicated.

“It wouldn’t have mattered whether it was a woven wire fence or a smooth wife fence or no fence: They couldn’t get through because of the snow,” he said. “And that’s something we don’t know how to address.”

An uncertain recovery

While Budd raised the possibility of relocating animals, Wyoming Game and Fish Director Brian Nesvik indicated in a June podcast that high-quality habitat will remain the key to a rebound. The Game and Fish also drastically slashed hunting licenses for mule deer and pronghorn and may boost tags for predators, which had a relatively easy winter. While some say the state should have fed deer and pronghorn, Nesvik said that’s not a feasible option.

“Be a little bit patient,” Gov. Mark Gordon said on The Morning Gather podcast. “Mother Nature has her time, and we can say we want to fix it, but she doesn’t often pay attention to us.”

At the Aug. 16 committee hearing, Monteith was reluctant to offer any concrete predictions for the future, as “we’ve kind of gone into the unknown.”

There are some glimmers of hope, he said, including the likelihood that the survivors will be “the fattest animals we’ve ever seen” heading into the winter. But as Monteith looks at the Wyoming Range mule deer herd, which had recently boasted 30,000 animals, “I suspect we’re well over a decade from ever getting back to where we were before,” he said.

“I think we will learn a lot through this process, hopefully,” he added, “but it’s an interesting and a tough spot that we’re going to be in for some time.”