Is It Time for Wyoming to Raise Minimum Wage to Help Workers Survive?

Legislators and business owners push back on more government regulation

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Jan 01, 2022

Raphael Brown, 42, earns $10 per hour plus tips at his job as a bartender at Creative Beverages in Gillette but manages to cover his living expenses through the help of government housing and food subsidies. Brown is one of 43,750 low-wage earners in Wyoming who make less than $15 per hour. (Photo by Mike Moore for the Wyoming Truth)

By Jennifer Kocher

Special to the Wyoming Truth

GILLETTE – For the first time in years, Raphael Brown loves his job. The 42-year-old native Virginian and single dad works as a bartender and liquor store clerk at Creative Beverages in Gillette.

Since arriving in Wyoming about eight years ago, Brown has held a handful of positions to make ends meet, working in the kitchen at a restaurant and deli, followed by a stint as an assistant manager at Family Dollar Store. Of all his jobs, Family Dollar paid the most in straight wages at $12 per hour.

In his new role, Brown brings in $10 an hour plus tips that are shared among the small staff.

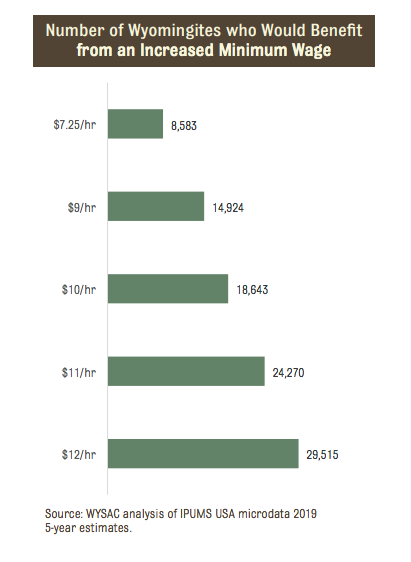

Brown is one of 43,750 low-wage earners in Wyoming who make less than $15 per hour, constituting about a quarter of Wyoming’s 175,000-person workforce, according to a December report from the Wyoming Community Foundation, a Laramie-based non-profit focused on social causes, that suggested raising the state minimum wage to $12 an hour. The report also called for raising the minimum wage for workers who receive tips from $2.13 to $6.85 an hour.

It’s new fuel for a debate growing in Wyoming and across the nation: What is an acceptable minimum wage for workers to survive financially?

The state’s minimum wage of $5.15 per hour falls under the federal minimum requirement of $7.25, making the Cowboy State one of the top five income-unequal states in the nation, per a 2018 ranking by the Economic Policy Institute, an independent think tank focused on economic trends and policies that impact U.S. workers. Teton County, in particular, led the pack as the most unequal county in the nation with the top 1% of the workforce making 142.2 times more than the bottom 99%.

In states like Wyoming where the federal wage exceeds the state minimum, employees must be paid the higher federal wage with some exceptions, including employees in the service sector earning tips, agricultural employees, those working on commission and others. Per state statute adopted in 2001, $5.15 is the lowest hourly wage that an employee can legally be paid in Wyoming.

Even so, full-time workers earning $7.25 per hour barely clear the federal poverty threshold. A minimum wage earner working 40 hours per week for 52 weeks per year earns $290 a week, or $15,080 annually before taxes. That’s just above the 2021 federal guideline, which sets poverty at $12,880.

Government welfare subsidizes the gap

To supplement his salary, Brown, the liquor store clerk, receives state and federal subsidies for housing and food.

As a single father of five children ages 5 to 21, his largest monthly expense is child support at about $550 per month. All of his children, except the youngest with whom he shares joint custody with the mother in Gillette, live out of state.

Thanks to a low-income housing subsidy program, Brown only pays about $300 a month compared to $700 to $900 in monthly rent he would otherwise pay. He also collects food stamps.

His job does not offer health insurance, so he goes without.

Without the subsidies, Brown said there’s no way he could afford to live on his earnings.

As Brown’s example indicates, it’s becoming increasingly harder for working adults to survive on wages in the face of a rising cost-of-living and inflation, according to Samin Dadelahi, chief operation officer for the Wyoming Community Foundation.

Statewide inflation has risen by 8% in the last year, per an October report by the state’s Economic Analysis Division. Nationally, the Consumer Price Index also rose 6.8 percent between November 2020 and 2021, the largest 12-month increase since June 1982.

The state’s minimum wage, by contrast, was last raised in 2001.

Because wages have not kept up with the cost of living, Dadelahi said, workers are increasingly having to rely on government assistance for help.

“These people are working hard,” she said. “It’s not as though they are working minimum-wage jobs because it’s easy.”

In the absence of adequate salaries, Dadelahi noted, increasingly more entitlement programs are stepping in to help fill those gaps.

“Why do we have so many entitlement programs?” she said. “Because we are artificially subsidizing these people.”

She points to the uptick of food support programs in communities across the state – in addition to First Lady Jenny Gordon’s hunger initiative ¬– to provide after-school and weekend snacks and meals for children and other programs designed to help families put food on their tables.

“Why in a state as wealthy as Wyoming do we have so many hungry families?” Dadelahi said.

In part, she noted, food becomes the answer because it’s the easiest and most immediate solution to a much larger problem in which workers are often forced to make tough decisions between medical care or paying rent.

The foundation’s recommendation to raise the state minimum wage to $12 per hour was based on a self-sufficiency calculator that researchers used to accurately take into account the various living costs in each of the state’s 23 counties.

The increased wage would have a great impact, Dadelahi said, and she hopes that state legislators take note of the report prior to the forthcoming legislative session.

Legislative help not likely

Efforts to raise the wage have been largely unsuccessful, former legislator Keith Goodenough believes, due to the state’s propensity for favoring businesses and low regulation.

Goodenough, a Democrat from Casper who served in the Wyoming House and Senate between 1989 and 2005, and most recently, as a Casper city councilman, said Wyoming’s minimum wage is woefully out of step with other states, most of whom have a minimum wage of at least $9 per hour.

Wyoming ties Georgia for the lowest minimum wage, followed by Minnesota at $6.15 per hour. Other states, by contrast, including neighboring Montana, tie their minimum wage to the consumer price index and periodically adjust it to keep up with inflation.

Goodenough cannot recall during his 14-year tenure when there’s ever been an appetite for raising the minimum wage, including a House bill last year sponsored by Albany County Democrat Karlee Provenza to raise the minimum wage to $15. The bill didn’t even make it to the floor for discussion.

The last substantial effort in 2014 – a bill to raise the minimum wage from $5.15 to $9 an hour and minimum wage employees who receive tips from $2.13 to $5 ¬– failed on first reading in the House by a vote of 51-9, according to a Wyoming Labor Force Trends report.

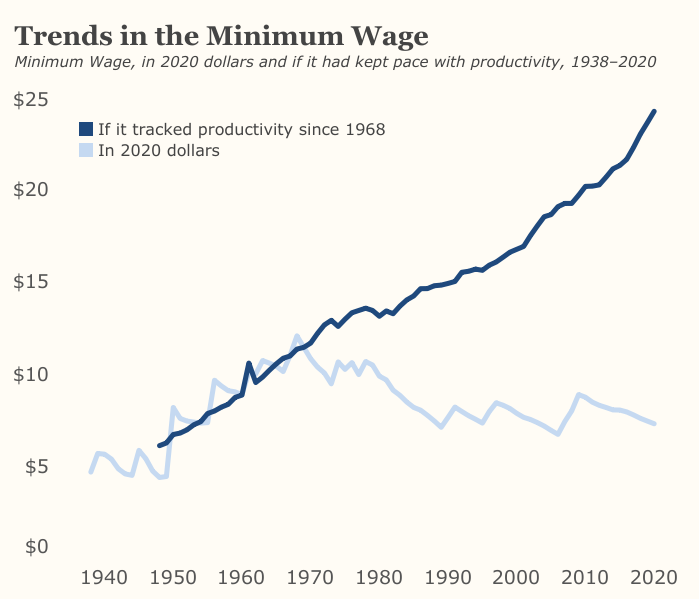

Goodenough would like to see the state’s minimum wage keep up with the cost of living, which he noted would be more than $24 an hour today, according to the Center for Economic Policy and Research, a global independent, non-profit agency that studies economic and social issues.

“Why is it such an outrageous proposal to have a minimum wage that keeps pace with buying power?” he said.

Business owner and state Sen. Troy McKeown (R – Campbell County) disagrees that government should raise the minimum wage, which he called a short-term solution that would lead to higher prices of goods and services.

McKeown employs 35 to 42 people at his two grocery stores in Wright and Gillette and pays well above the minimum wage though he didn’t want to specify how much.

If businesses raised their minimum wage to $15 per hour, he said, consumers would see an immediate increase in cost with hamburgers going for $7 instead of $5. Small business owners would find it hard to eat the additional cost in wages, he said.

He thinks the government stepping in is the worst thing that could happen.

“A lot of the problem is that the government is too involved,” he said. “Inflation has grown the fastest in any of the sectors involving the government.”

Labor demands pushing wages up

Opponents of raising the minimum wage argue that worker shortage and a rapidly dwindling unemployment rate statewide are doing a good job at setting wages. In November, Wyoming’s unemployment rate fell to 3.7%, down from 4.1% the month prior, according to the Wyoming Department of Workforce Services.

Sixteen counties saw a decrease in unemployment, according to the report, while unemployment went up slightly in four other counties with three remaining unchanged over the previous month.

The low-unemployment rate has forced many companies, including those in fast food, convenience stores and restaurants, to raise wages to attract elusive workers.

Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, for example, recently raised its starting wage to $18 per hour. This increase followed upping the minimum wage from $13.50 to $15 in September to stay competitive with other ski areas, according to Eric Seymour, director of brand communications and content for the resort.

Other national chains like Hobby Lobby have raised their starting wage to $18.50 an hour, including its three stores in Cheyenne, Casper and Gillette.

Business storefronts throughout the state are plastered with help wanted signs with more openings advertised on the Wyoming Workforce Services job website.

Most of the jobs start at about $10 an hour, including a store associate opening at Zander’s One Stop convenience store in Lander, a $11-per-hour housekeeping job at a hotel in Douglas and a $12.58-per-hour cook position with the Laramie County School District. Wait staff positions, too, are offering starting wages well beyond the minimum at $7.25 and $10 an hour plus tips.

Some, like Brown’s manager at Creative Beverages, 33-year-old Veronica Koch, wondered if increasing wages will be enough to attract workers to fill job vacancies across various industries or if there’s more to the problem.

She’s struggled to find workers who actually show up to work, regardless of raising the starting wage.

“People just don’t seem to have a good work ethic anymore,” she said.

Regardless, she said it’s inevitable that the state minimum wage will be raised, which would likely mean cutting a few positions and picking up more of the work herself.

“We could handle it,” she said, “but we’d have to cut some jobs.”