Mormonland: Church and State in the Equality State (Part 2)

Some question LDS church's land business in real estate, given the religious organization's tax-exempt status

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Feb 07, 2023

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' Church Office Building in Salt Lake City. (Courtesy photo from Ricardo630 via Wikimedia Commons)

By Sarah Scoles

Special to the Wyoming Truth

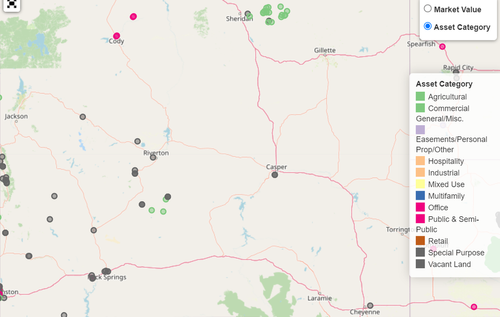

The state of Wyoming encompasses around 62.3 million acres of land. And nearly 100,000 of them belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also known as the Mormon or LDS church. Much of the land is agricultural. Some of it is historically significant, although Wyoming is also dotted with real estate in the form of church meetinghouses and other facilities.

According to data first gathered by the nonprofit Truth & Transparency, the church’s American property portfolio is worth at least $15.7 billion and spans at least 1.75 million acres nationwide.

In Wyoming, Truth & Transparency’s work suggests the church owns about 33,627 acres,

26,694.35 of which are in Sheridan County. A Wyoming Truth analysis of assessors’ databases in the three counties in which Truth & Transparency uncovered the most owned acreage, however, brings it closer to 100,000, with around 85,830 acres in Sheridan County, 7,770 acres in Natrona County and 3,190 acres in Uinta County. Most of the large plots are agricultural.

The magnitude of LDS real estate brings up questions about the church and the state. While the church pays Uncle Sam for the land it owns — and so contributes to Wyoming’s budget — the money the organization collects from members, in the form of tithing, is tax-exempt. It doesn’t have to pay up on the initial capital that it may use to buy the land.

“The church has access to untaxed resources,” said Ryan McKnight, co-founder of Truth & Transparency. “It makes them a more powerful negotiator than the entity that doesn’t.”

When a church has so much money and invests it in real estate to make more money, it also feels different from when a corporation has or does the same things. “That’s where the eyebrows start to raise,” McKnight said. The way the church buys property, in Wyoming and beyond, he said, suggests “the idea that the church is a business that dabbles in religion, as opposed to what they want you to believe, which is that they’re a religion that dabbles in business.”

That’s always been a bit true. “The church was never just a church,” said Patrick Mason, Arrington chair of Mormon history and culture at Utah State University. “From the very earliest years, it had its fingers in local politics and in real estate.”

Around the Mormon pioneers’ trek West and inhabitation of what some today call the “Jell-O Belt,” much of that land acquisition was typical frontier settlement.

“Before Wyoming became a state, the LDS people were migrating to the Salt Lake Valley,” said Tony Young, former Gov. Matt Mead’s deputy chief of staff, and a member of the LDS church. “And across Wyoming, church members built settlements.”

Early LDS people, for instance, helped found the towns of Afton, Auburn and Bridger Valley, among others. “Wyoming — particularly Western Wyoming and northwestern Wyoming — had a very strong contingent of LDS members that were settled or homesteaded in those areas,” said Young. “And it grew from there.”

Settled in the West

Near the turn of the 20th century, Wyoming’s then-governor encouraged the church to send a colonization company to settle the Bighorn Basin, and they did exactly that, through the aptly named Big Horn Basin Colonization Company.

“They were masters at digging canals, and they knew how to irrigate, and so there was a lot of need for that,” Young said. Today, over 67,700 LDS members, around 11.7% of the state’s total population, call Wyoming home, according to church spokesperson Joseph Tateoka.

But the game started to change once the West was won. “In the mid 20th century, and especially now, it’s much more of an investment model,” said Mason. “It’s no longer the church buying land for people to settle on. It’s the church buying land to develop in various kinds of enterprises…It’s an investment in the church’s long-term financial stability and prosperity.”

There is disagreement, though, about how much prosperity a church should have. Some claim the church has resources commensurate with its membership numbers and goals, Mason noted. “Whereas other people say, ‘Well, this is not a private company; this is not a corporation,’” he continued. “‘This is a church, and churches are meant to serve the public good. And so it is obscene for the church to have investment portfolios in excess of $100 billion dollars and invest in massive tracts of land and other kinds of real estate.’”

In Mason’s mind, as a practicing Mormon, it’s a legitimate debate.

Mason said most church members have an implicit trust in church leaders and the organization’s resource-handling. But that percentage is shrinking.

“There’s clearly a growing chorus of voices, still very much in the minority, who are quietly and openly asking the question, ‘How much is too much?’” he said.

The question of LDS land ownership, said Mason, is one way to dive into larger issues in American culture and policy. What is the role of churches in society? How do we think of transparency? “Those are big, huge questions that are really important to think about, and Mormonism is just one way in,” he said.

That’s true anywhere, but especially in Wyoming, which has the third-largest LDS membership, in terms of percentage of population, and whose existence is so tied to its landscape — and whose landscape is so tied to wealth.