Seeds of Hope for Threatened Pine Species

New strategy launched to restore whitebark pine in Grand Teton National Park

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Oct 15, 2023

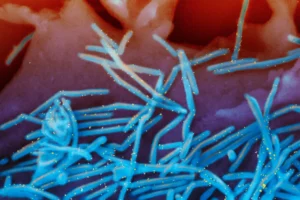

Crews planted 3,000 whitebark pine seeds in the Tetons in late September, the beginning of a five-year partnership among the National Park, American Forests and the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative to restore populations of the high-altitude conifer. (Courtesy photo from the National Park Service)

By Melissa Thomasma

Special to the Wyoming Truth

Whitebark pine, a native species of high-elevation conifer, is on the brink of decimation. Populations have declined 50% across their endemic range and crashed by a startling 85% in Grand Teton National Park, the Northern Rockies Conservation Cooperative (NRCC), a Jackson-based environmental nonprofit, reported.

And the tree was even listed as “Threatened” under the Endangered Species Act in December 2022.

Now, a new glimmer of hope has emerged: the National Park Service, the NRCC and American Forests are implementing a reseeding strategy to restore whitebark populations. The project’s funding comes from the $44 million Inflation Reduction Act, the largest climate and conservation investment in history, in alignment with the Department of the Interior’s America the Beautiful initiative to restore and conserve 30% of lands and waters by 2030.

Since 2000, over 75% of mature whitebark pine trees have been killed by mountain pine beetle, and about 20% of the remaining live trees are infected with white pine blister rust — an invasive fungal disease introduced in the early 1900s — Elisabeth Pansing, director of forest and restoration science for American Forests, told the Wyoming Truth.

Pansing is leading the project implementation with NRCC researcher Nancy Bockino and Laura Jones, branch chief of vegetation ecology and management for Grand Teton National Park.

Bockino’s whitebark research, which has spanned two decades, led her to connect Pansing with ecologists at Grand Teton. Starting in September, the team implemented a strategy to change the trajectory of whitebark pine in the Tetons. At the core was Pansing’s research that upended conventional wisdom: planting whitebark seeds — instead of pre-started seedlings — actually does work.

Whitebark pine is considered a keystone species, and its disappearance has dramatic impacts on the wider ecosystem, Jones told the Wyoming Truth. As one of the first species to grow in tough high-altitude conditions, whitebark improves soil quality for other plants, slows erosion and captures carbon.

“It’s a special tree because of where it grows; it’s like a ‘rooftop’ to the Rockies,” Bockino said. “Its most important job is to capture and shade snow… If there were no trees, our snow capture and melt would be very different.”

This slow-growing species can take three years to germinate and another decade to achieve mere inches or growth; the largest in the Rockies are around 1,000 years old.

Bockino and her team laced up their hiking boots and hit the trails of the Tetons in September, covering 1,800 trail miles and 470,000 vertical feet. “My crew planted and GPS-marked about 1,400 sites; the whole project included around 3,000 seeds,” she said.

The team will return to these locations in subsequent years to monitor the seeds’ growth. Some seeds were planted at a nursery in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, and will be ready for planting in the fall of 2025, added Jones.

“Success will mean that we’re increasing capacity to restore whitebark pine in remote and challenging locations,” Pansing said.

And increasing the number of disease-resistant seedlings on the landscape will prepare forests to withstand the impacts of blister rust long-term.

There are a few aspects of success that Pansing will be eyeing. “Restoring whitebark pine across its range will require collective action — we need all hands on deck,” she said. “We’re already succeeding here. Additional metrics of success will include active restoration via direct seeding, as well as a better understanding of how we can improve direct seeding as an operational restoration tool.”

One tool among many

Grand Teton National Park also operates ongoing programs to study and protect the trees that are still alive. The park has long been placing verbenone pouches on trees with demonstrated resistance to whitebark pine blister rust, Jones said.

Verbenone, which is a pheromone, signals to beetles that a tree is occupied and cannot sustain more beetles. “Monitoring of those trees show that less than 5% have been invaded and killed by beetles,” Jones said.

Another tactic is stripping bark from dead trees before the new adult beetles fly to reduce their infesting the next tree. This plan is a lighter touch than cutting and burning dead trees, Jones said, but isn’t always a feasible in the Tetons where access is difficult.

This constellation of tactics, in addition to growing the next generation of whitebark pine, gives experts hope.

“Despite its recent listing as ‘Threatened’ under the Endangered Species Act, this species will recover,” said Pansing. “We have the knowledge, the tools, the plans and a devoted group of people leading the way. We know what to do; we just need to execute it.”

Bockino agreed, casting trees as the planet’s strongest hope. “If you step back and think about the state of the affairs around the world, trees take CO2 and make oxygen, which is like magic,” she said. “They’re literally saving us from ourselves.”