Switched at Birth: Decades After Discovery, Gillette Woman Forges New Life (Part 1)

After years of silence and shame, Shirley Muñoz Newson shares her story of being raised in the wrong family

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Nov 11, 2023

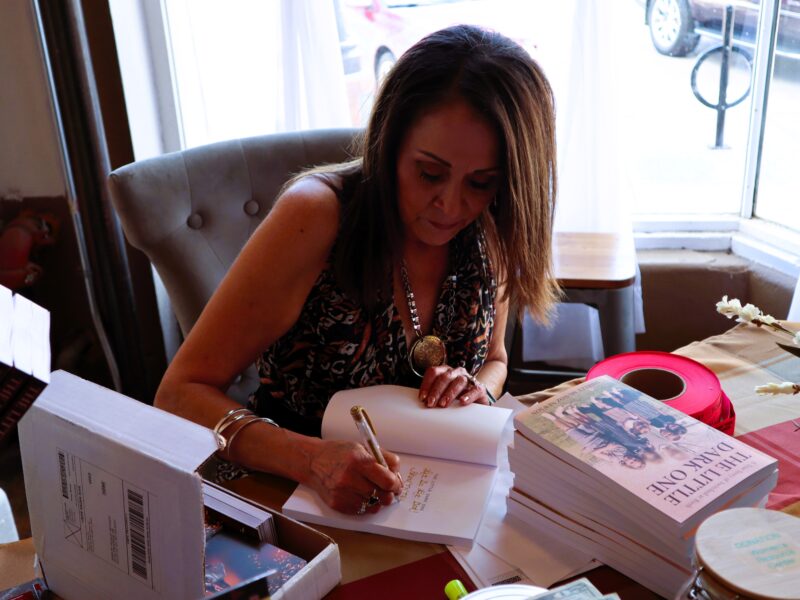

Shirley Muñoz Newson signs copies of her memoir, "The Little Dark One," following a reading in July in Gillette. (Courtesy photo from Shirley Muñoz Newson)

By Jennifer Kocher

Special to the Wyoming Truth

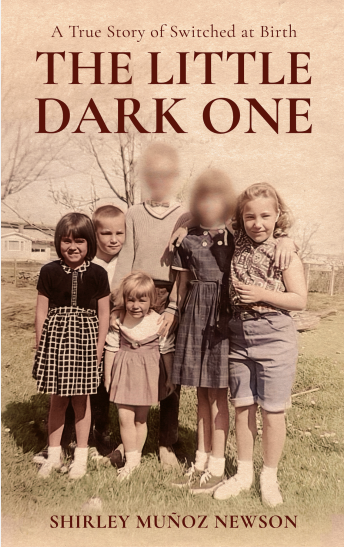

Shirley Muñoz Newson released her memoir, “The Little Dark One: A True Story of Switched at Birth,” in July. In her first in-depth interview since the book’s release, she spoke with the Wyoming Truth about her life and what it means for her to finally find her voice.

GILLETTE, Wyo.– As a child growing up in the early 1960s, Shirley Muñoz Newson

heard the jokes and felt the stares from residents in her small hometown of Gillette.

Petite and brown-eyed with olive skin, Newson didn’t resemble the seven other children in the Morgan family. All were of Irish descent—tall with light eyes and skin and red hair.

Rumors abounded, including within her own family.

The man who raised her, James “Jim” Morgan, eyed Newson’s physical differences with mistrust, openly and frequently questioning the fidelity of his wife, Jean. Many in the community agreed Newson’s appearance could mean only one thing: Jean cheated.

Jean, meanwhile, told Newson she looked like her paternal French-Canadian grandmother.

Newson, now 65, had no words for the alienation and shame she felt as a child. It didn’t make sense to her, only that she didn’t resemble her parents or siblings. Nor were the Morgans kind to her, Newson said, with the exception of her younger brother, Bill, and her older brother, Gerey, who died when he was 22.

Newson recalled an early rejection as a toddler when she accompanied Jean on errands. Spooked by a bumblebee outside the post office, she asked to hold Jean’s hand. But Jean refused.

“It’s dirty and sweaty,” she told Newson, turning away.

Jean also told Newson that she talked too much and needed to learn to keep her thoughts to herself, Newson recalled.

When Newson was 13, Jean insisted she read a letter from James’ mother in which she used a racial slur to refer to Newson. The rebuffs sent Newson inward, and she learned to stifle her emotions.

“As a kid, you just adapt and deal with the day to day, so you don’t question it, even at times when it’s so hurtful,” Newson said.

Close for a time

In 1976, Newson’s relationship with Jean and her oldest sister, Hilda, improved when she graduated from high school and discovered she was pregnant—a month after her boyfriend called off their engagement. Newson had been terrified to tell the Morgans, but they took the news in stride, offering to support both she and the baby. After her son, Chris, was born, Jean and Hilda watched him during the day while Newson worked as a receptionist at the hospital. For the first time, Newson felt like she belonged.

It didn’t last long, however. The relationship was once again frayed when Newson announced her engagement to Barry Larsen and plans to move to Rawlins. Hilda wrote Newson a four-page letter, explaining why she felt Newson was making a mistake and asking for guardianship of Chris, then age 3. Newson refused.

The Larsens eventually moved back to Gillette and had two more children, Lindsay and T.J. Barry started an oilfield company and Newson worked in accounting for a surgical clinic. They socialized mainly with the Larsen family, though the Morgans retained close relationships with Newson’s three children. After a 13-year rocky marriage, the couple divorced in 1993.

Truth revealed

In 2001, Newson finally learned the truth of her parentage. At the end of his life, James asked Newson to take a DNA test to determine her paternity. He wanted answers before he died, he told her. She happily agreed and received the results on the eve of her 43rd birthday.

Nobody, except perhaps Newson herself, was shocked by the news: James had a zero percent chance of being her father. A second test also revealed Jean was not her biological mother. Newson’s DNA showed she was of 32% Indigenous Mexican American descent and 68% European.

James told Newson he always knew she was not his biological child, but decided to raise her anyway. That’s what ranchers do, he explained.

“It’s just like when a bum lamb with a black face is raised by another ewe,” he told Newson. “She just takes it in, even though she has a black face, and raises her. That’s what I did with you.”

James and Jean’s response was not surprising to Newson, though it was hurtful, she said. Neither told her that she was their daughter regardless of the DNA test results. Instead, Newson said, they eagerly began searching for their biological daughter.

Swapped at birth

It was inconceivable to Newson that she could have been switched at birth, she said. But it was the only explanation—and it rocked her world.

How does this happen? According to the DNA Diagnostics Center, an Ohio-based genetic testing laboratory, of the up to 500,000 babies born each year in the United States, only 18 may be switched at birth and most of them are caught immediately following the incident.

Between 1995 and 2008, the laboratory’s statistics found that eight newborns were switched in the U.S., though this figure might be higher because there is no national mandate for hospitals or individuals to report such incidents.

For Newson, it took hiring a lawyer to file a court petition and hours of research scouring hospital birth and state medical records to get answers.

According to hospital records obtained by Newson, Jean was the only birth mother who was admitted on April 8, 1958, and Newson’s birth the only one officially recorded, just after 3 a.m., at Campbell County Memorial Hospital—then run by Banner Health.

It turned out Newson’s unwed birth mother, then 20-year-old Polly Leyva (now Muñoz), was not documented on the formal registry. In 1958, as Newson learned, unwed mothers were segregated from married mothers in a separate birthing area, and their babies were not publicly announced. Muñoz’s patient file, later reviewed by Newson, revealed Muñoz had received no prenatal care and had walked by herself to the hospital in the middle of a snowstorm.

In 2003, Newson toured the former hospital — which had been converted into the former Gillette College — with two retired nurses. Irene Hubbard and Rosemary Shober, who worked there in the late 1950s, were shocked to learn the switch had occurred, Newson said.

The former nurses told Newson that pregnant women were given Demerol during delivery in the 1950s, after which the babies were shuttled away to be cleaned, weighed and measured in separate nurseries. The newborns were then tagged with identification bracelets, the letters of their last names printed on beads that were threaded on elastic bands.

Muñoz had a traumatic delivery that required several blood transfusions and four shots of Demerol, according to medical records reviewed by Newson.

One nurse speculated that the switch may have been a result of misplaced charts, according to Newson. This made no sense to her, and she inquired how a dark-complected baby of Mexican descent could have been switched with a white baby without the mothers noticing. Newson further wondered how neither mother would have seen the other in such a small space or asked any questions.

The nurses had no answers.

Court battle

Neither did Banner Health. The health care organization denied all responsibility for the switch after Newson and Muñoz filed suit in the Wyoming Supreme Court to determine whether they could legally sue Banner Health for purely emotional damages. During the court hearing in April 2003, the hospital’s attorney postulated that the two babies may have been switched by a stranger off the street or by a doctor playing a joke.

Prior to Newson’s lawsuit, there was no court precedent in Wyoming that allowed for the recovery of emotional damages due to negligent actions brought forth by an individual who was switched at birth. Newson’s case carved out this exception for future lawsuits to be filed, according to a December 2003 Wyoming Supreme Court decision.

Both women ultimately settled with Banner Health for undisclosed sums.

“You can argue that my life might not have been any better in my biological family, but that question can never be answered,” Newson said during the mediation proceedings in September 2004. “Your mistake changed my life forever.”

Newson finally knew the truth, but she had no idea how that knowledge would shape the next 20 years of her life.

Check back for part two, coming soon.