Tangled Jurisdiction, Understaffed Police Department Blamed for High Crime Rate on Wind River Indian Reservation

Advocates call for more police funding and clearer jurisdictional boundary lines

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2023

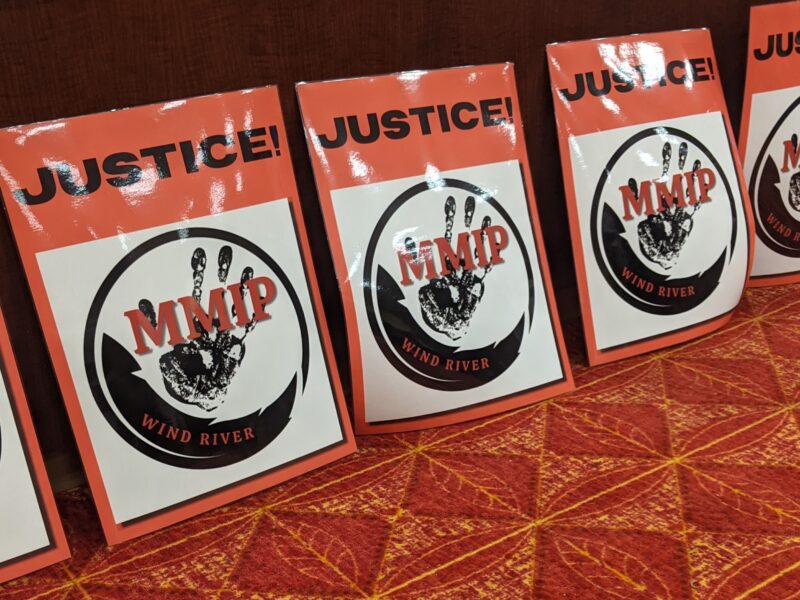

Statistics show that Indigenous people are disproportionately impacted by violent crimes than other ethnicities. In 2020, the homicide rate for Indigenous women was 10 per 100,000 people, nearly six times higher than the 2.3 per every 100,000 for White females according to the Wyoming Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force’s 2023 report. (Wyoming Truth photo by Jennifer Kocher)

By Jennifer Kocher

Special to the Wyoming Truth

RIVERTON, Wyo.-The stories speak for themselves. One by one, nearly a dozen citizens from the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapahoe Tribes stood up to share their stories of missing and murdered relatives at the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force meeting last month on the Wind River Indian Reservation.

One man asked for prayers for his younger brother, who disappeared in February 2018. The family posted on social media and even hired their own private investigator in an attempt to bring him home. Police have done the bare minimum to search for him, he said.

“Where did he go?” the man asked. “People don’t just disappear.”

A woman shared the story of her older sister’s unsolved murder dating back nearly three decades. She was tortured before she died. To date, nobody has gone to jail.

The stories go on, supporting statistics collected by the Wyoming Survey and Analysis Center showing that Indigenous people are disproportionately more impacted by violent crimes than other ethnicities. In 2020, the homicide rate for Indigenous women was 10 per 100,000 people, nearly six times higher compared to the 2.3 per every 100,000 of White females, according to the Wyoming Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force’s 2023 report.

Meanwhile, the National Institute of Justice reported in 2016 that 84% of Native Americans and Alaska Native women have experienced some form of violence in their lifetime. And 56% reported sexual violence.

Indigenous males fared even worse: The same report found that 26.4 of 100,000 Native American men were victims of homicide compared to 4.2 per 100,000 White men.

Indigenous people are much more likely to go missing than their White counterparts. In 2021 and 2022, 360 reports were created for 216 Indigenous people (some people went missing more than once) from nine counties in Wyoming, statistics from the National Crime Information Center show.

Bound by court precedent, federal statutes

The question remains: why are Indigenous people much more prone to be victims of crimes?

The answer is simple or complicated based on one’s point of view, according to Sara Robinson, senior staff attorney for the Wyoming Coalition Against Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault and member of the Eastern Shoshone tribe. For Robinson, the root cause is steeped in history, beginning with the European colonization that kicked off years of “ruthless violence” and “racism” against Indigenous peoples.

“The picturesque backdrop is set on the enormous legal jurisdictional tangle of SCOTUS [Supreme Court of the United States] precedent, treaties and federal statutes that muddy the waters,” Robinson said.

Despite being a sovereign nation, Indian tribes are subject to federal laws and oversight under the 1817 General Crimes Act, as well as the Constitution itself that gives Congress the power to define and punish all offenses under the law.

The Wind River Indian Reservation, which encompasses 2.2 million acres, falls under the jurisdiction of the Wind River Police Department. This agency is overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) officers and only has authority to arrest tribal offenders.

The right to arrest only tribal members is the result of a 1978 Supreme Court decision, Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, that stripped tribes of the authority to prosecute non-natives on reservation lands due to “actions and behaviors that were abhorrent and overreaching to trespassers and thieves entering Indian County.”

Over the years, the Wyoming Legislature has attempted, but failed to pass laws restoring these rights.

Wind River has its own tribal court that prosecutes tribal offenders who violate criminal misdemeanor violations and provides a court process for civil legal matters based on the Law and Order Code of the Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes.

More serious crimes like murder, rape, incest, felony child abuse, assault with intent to kill and others fall under federal jurisdiction; they are investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and prosecuted by the U.S. Attorney for the District of Wyoming.

“Problems arise on the other side of the reservation perimeter boundary,” Robinson said, “with violence off the [reservation] in the border towns of Lander, Riverton and Thermopolis.”

In recent experience, Robinson said allegations of violence perpetrated against tribal women by their non-tribal partner were either found to be trivial and not thoroughly investigated or dismissed by the Wyoming U.S. Attorney’s Office due to lack of evidence or witnesses.

“A local violence advocate organization said that over a year’s time [in 2022], 268 survivors came through their doors seeking refuge and help,” Robinson said. “Only one survivor was provided a legal avenue to pursue her aggressor.”

Similarly, Robinson said response time is also an issue given that there are only 16 BIA officers patrolling the entire reservation. As such, it might take anywhere from minutes to hours to respond if they show at all.

Another safety issue, Robinson noted, is the victim’s propensity not to report their abuser.

“If they have not been injured enough to warrant a hospital visit, they won’t say anything,” she said. “Through their own basic rights, they are not obligated to report how it happened, what happened or who did it.”

Tangled jurisdiction

One outspoken advocate, 35-year-old Letara LeBeau, is a member of the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone tribes and sits on the state’s Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force.

LeBeau, who hails from Crowheart, said crime on the reservation has been a major problem for the past 25 years. In her mind, it stems from a lack of police presence, jurisdictional issues and an unwillingness on behalf of the tribal court to prosecute offenders.

“Our judicial system needs to be revamped 100%,” said LeBeau, who was recognized as one of USA Today’s “2023 Women of the Year” for her contributions to the Native American community in Wyoming.“Nepotism plays a huge part, because everyone is related to each other [on the reservation].

LeBeau said that criminal complaints are not prosecuted equally. She would also like to see equal protocols for all within the tribal system. She’s also calling for an emphasis on prevention, cultural sensitivity on behalf of all law enforcement and advanced training and agreement on jurisdictional issues.

“We have to clean up this mess,” she said. “Leadership needs more transparency.”

The boundaries can be a real stumbling block when it comes to prosecuting crimes. LeBeau referenced a woman who recently reported that her car had been stolen by the man who was physically abusing her. The car was taken from the reservation, but parked and abandoned in Lander. Because the car was not on reservation land, it wasn’t a BIA issue. However, when the woman called police to report the stolen car, the police kicked it back to the BIA because it had been taken off reservation land.

As agencies bickered back and forth, LeBeau said, the victim was left hanging in the crosshairs.

“She was desolate and trying to flee for her safety,” LeBeau said. “Meanwhile, the individual steals her vehicle, which is in her name, but it comes back down to residency and the BIA.”

Initiatives in the works

Some efforts have been made on the national level. U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, the nation’s first Native American cabinet secretary, announced in April the formation of a new Missing and Murdered Unit within the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The unit is tasked specifically with investigating missing and murdered cases of Native Americans and Alaska Natives with access to marshal law enforcement resources throughout federal agencies.

Ultimately, though, Robinson believes solutions need to come from within the Indigenous community.

“It has to be our work,” she said. “I think the first step is to engage the people and the communities who are affected. The leadership has to be invested in solutions, and we need to band together. All of us.”