UW Researchers Discover Evolutionary Adaptation in Trout in Wyoming’s Wind Rivers

Fish evolved to adjust to smaller food supply, study says

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Aug 27, 2023

Lucia Combrink, the study’s lead author, collects data on the Yellowstone cutthroat trout. (Courtesy photo from Lucia Combrink)

By Shen Wu Tan

Special to the Wyoming Truth

What do you do if your environment has a shrinking food supply?

Well, if you’re a trout in the Winds Rivers, you evolve to adapt to your environment.

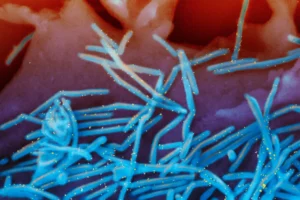

University of Wyoming researchers have discovered that trout in the alpine lakes of Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains developed more gill rakers, which are bony or cartilage structures in the gullets of fish that retain zooplankton and nourish the trout, according to a study published in the journal Evolution last month.

Trout were stocked in the early 1900s in the lakes of Wind River Mountains, which historically didn’t host fish. The fish populations have grown over the last century in hundreds of these lakes; their presence has reduced the size of zooplankton, small aquatic organisms that trout feed on, previous research has revealed. But the fish have undergone a “rapid evolution” and adapted to their environment to feed on smaller-bodied zooplankton more efficiently, UW researchers say.

“Whether climate change or other disturbances caused by anthropogenic (human) impact, one of the most pressing issues facing natural ecosystems is the incredibly rapid pace of ecological change,” Lucia Combrink, the study’s lead author, told the Wyoming Truth.

“Huge changes are often happening to natural environments more quickly than organisms can respond and adapt to survive, but this research study provides an example where some populations of trout have adapted to a novel habitat via a change in feeding morphology rather rapidly—over the course of just a few generations…. Such examples of rapid adaptation are hopeful. They indicate that populations can sometimes respond quickly to contemporary ecological change.”

Researchers also examined how the ecosystem has changed in the previously fishless alpine lakes, where anglers seek golden trout and cutthroat trout.

“The significance of the finding is that it confirms our belief that fish adapt to their environment and that stocking should be limited to systems where reproduction is limited or does not occur,” said Joe Deromedi, Lander Regional Fisheries Supervisor for the Wyoming Game and Fish Department.

“Most wild fisheries are managed to preserve the genetic adaptations of that population. When Game and Fish considers restoring native trout in streams, we consider using neighboring populations—fish that would have similar genetic adaptations.”

The study’s lead author, Combrink, earned a master’s degree from UW’s Department of Botany and is now a Ph.D. student at the University of British Columbia. Other authors include Catherine Wagner, an associate professor in UW’s Department of Botany; Amy Krist, an associate professor in UW’s Department of Zoology and Physiology; and Annika Walters, an associate professor and assistant unit leader of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Wyoming Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at UW.

Current UW postdoctoral students and UW graduates also contributed to the study, including Elizabeth Mandeville, Jessica Rick, Lindsey Boyle and William Rosenthal.

‘Exciting questions remain’

The researchers collected over 200 cutthroat trout and nearly 130 golden trout from 18 lakes in the Wind Rivers, which were stocked with these fish, during the summers of 2018 through 2021.

The lakes had more recently stocked fish populations and groups from decades ago. These fish were then compared to the golden trout and cutthroat trout from the Wyoming Game and Fish Department hatcheries.

Surveys of fishless lakes in the area indicate that these alpine lakes contained large-bodied zooplankton before the stocking of fish populations, the study’s authors wrote. However, since stocking, there’s been a “shift to smaller-bodied zooplankton species” due to “size-selective predation,” a finding observed elsewhere.

The higher number of gill rakers found in the Wind Rivers’ trout likely resulted from the fish adapting to the food sources of high-mountain lakes. The change occurred in a short period of time, relatively speaking, and aligned with the timing of the stocking of the lakes.

Combrink said researchers also believe the changes in the gill rakers are linked to changes in the genome, because these features are “highly heritable from one generation to the next.”

Research in the Wind River Range’s alpine lakes is still underway, with more questions about the ecology and evolution of organisms in these environments to be answered, Combrink noted.

The questions include: To what extent have other stocked fish populations in Wyoming adapted to new environments? Why do some fish populations make it, while others don’t? How else can trout and other fish quickly evolve when facing ecological pressures? How can theories from evolution be applied to save populations from extinction in a rapidly changing world?

“To me, this study feels like the start of an exciting journey,” Combrink said. “Our team has documented evidence for rapid adaptation of gill rakers [feeding structures] in these trout populations, but lots of exciting questions remain.”