Wyoming Fire Watch: No Major Wildfire Incidents… Yet

Fire danger elevated across the state with rain in the forecast

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Aug 04, 2023

A lightning strike ignited a small fire on the southern edge of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort during a storm on July 24. Dubbed the Rock Springs Fire, experts at the Bridger-Teton National Forest are watching it closely, and public affairs officer Mary Cernicek said that as of August 1, the fire has largely self-extinguished. (Courtesy photo from the Bridger-Teton National Forest)

By Melissa Thomasma

Special to the Wyoming Truth

With the arrival of August, the Rocky Mountain West moves into peak wildfire season. Large and intense blazes rage from California through the Pacific Northwest and into Canada, but much of Wyoming is rated at “high” fire danger. There are no active incidents within the state, according to InciWeb, the federal emergency incident reporting system.

As the impacts of climate change exacerbate fire season globally, summertime weather patterns are a major factor in wildfire risk.

“Our fuels are susceptible and ready to carry fire,” Mary Cernicek, public affairs officer for the Bridger-Teton National Forest, told the Wyoming Truth.

Incoming monsoonal rain patterns are welcome for the moisture they will bring, she said, but there’s no guarantee human negligence or aggressive lightning won’t spark a challenging blaze.

The National Interagency Fire Center reported on August 1 that 30,466 wildfires have burned 1,174,562 acres in the United States to date in 2023. Of those, 2,500 were ignited by lightning, while over 27,850 were caused by humans.

“Being in the ‘high’ fire danger rating means that fires can start easily and small fuels like grasses or pine needles will ignite readily,” Cernicek said.

Two multi-acre fires in the past 10 days merited multi-day responses from firefighters across the state, but both have been subdued as of the first weekend in August.

Sixteen miles northwest of Torrington, the Pine Ridge Fire burned around 560 acres since it was first reported on July 25 and is considered fully contained by the National Interagency Fire Center. To date, the agency said, the price tag for the fire is estimated at $1 million.

The Chaffie Fire, approximately 40 miles east of Sheridan, was reported on August 1 and burned just over 375 acres. According to the National Interagency Fire Center, the blaze is fully contained.

The state also has experienced a handful of small fires — both with natural and human ignitions — that were rapidly identified and extinguished, keeping them below a single square acre based on data tracked by the nationwide nonprofit Fire, Weather and Avalanche Center.

Hotter than normal?

Shorter, warmer winters and longer, hotter summers are a key reason for increasingly intense wildfires across the globe, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Headlines highlighting record-shattering high temperatures nationwide have grabbed attention. But was Wyoming superheated in July?

Lance VandenBoogart, meteorologist for NOAA based in Riverton, said the answer is both yes and no.

“It hasn’t been a record hot summer so far,” he told the Wyoming Truth, “but it has been slightly above normal.” He cited data indicating the western and central parts of the state averaged about three to five degrees above normal for most of July.

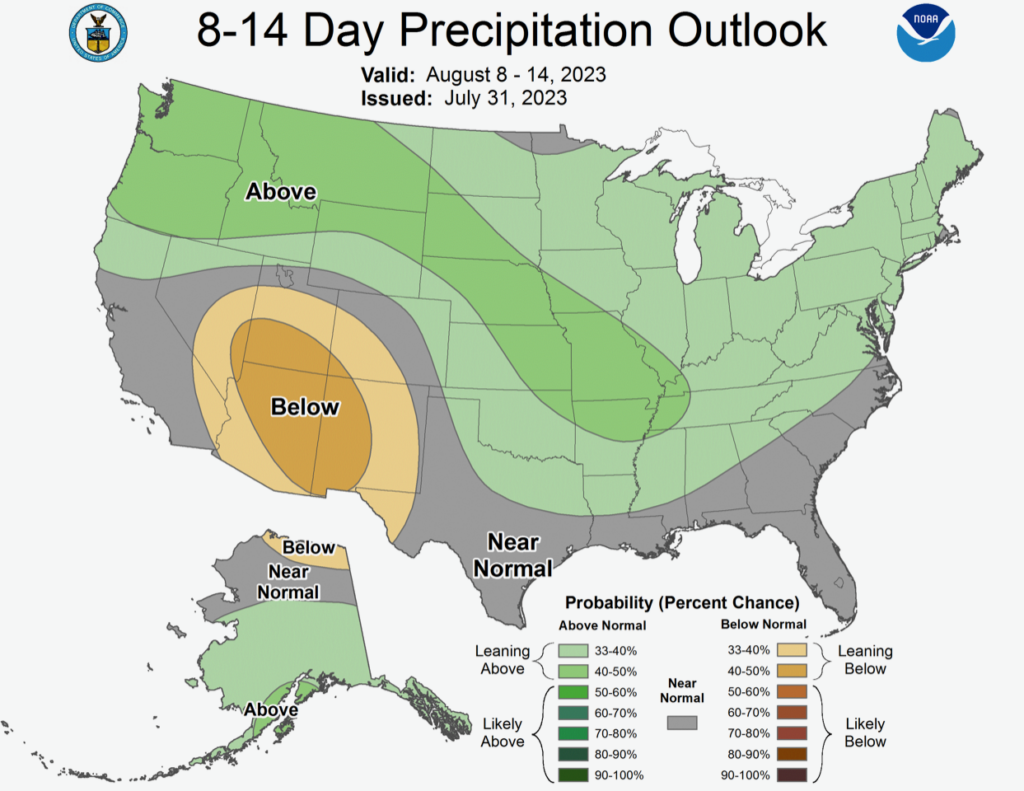

“We have a monsoonal pattern coming in for the next couple of weeks, pulling moisture from the Pacific and Baja over the desert Southwest, and we’ll get some of that moisture in Wyoming,” VandenBoogart said. “More moisture does equal more thunderstorms, but monsoonal storms aren’t as dangerous in terms of lightning.” Any lightning that is produced by thunderstorms is likely to be accompanied by sufficient rainfall to prevent or quickly extinguish lightning starts.

Looking further ahead, VandenBoogart said climatological models don’t indicate Wyoming’s weather will be extreme in one way or another through the duration of fire season.

“There appears to be a slight lean towards warmer than normal in the coming two months, which could lead to a slightly elevated risk of fire,” he said, noting all predictions fall within the realm of average.

The human factor

Large, dangerous wildfires don’t require extreme weather to start or spread. One of the Rocky Mountain region’s largest fires in 2022 — the Moose Fire near Salmon, Idaho — began on July 17 from an unattended campfire and actively burned until snowfall, devastating over 200 square miles. Fire officials for the Salmon-Challis National Forest made a startling discovery in late June: a large dead tree was still smoldering from the previous summer’s blaze, “enduring winter weather to continue burning.”

Cernicek said this unexpected burning material, which was found nearly a year after the fire’s ignition, is a reminder about the lasting impact wildfires can have on the landscape. She pointed out that while Wyoming is not experiencing extreme fire weather at the moment, many factors contribute to the status of “high” fire danger in the western part of the state.

The heavy winter and slow spring warm-up gave grasses and shrubs plenty of time to grow, she said, and now the summer heat and winds are drying them out — a potentially dangerous combination.

Both within the Bridger-Teton National Forest and beyond, Cernicek encourages all forest users to be aware of fire danger ratings and restrictions — of which there are none currently in place — in addition to weather forecasts.

“It is so important to thoroughly extinguish campfires,” she said. “All it takes is an afternoon breeze to blow those embers that weren’t all the way cold. Fires can start easily in small fuels.”

Cernicek added that summer conditions can also make wildfires more difficult to fight, especially on steep slopes or in areas with concentrated fuels. Users should always extinguish campfires until they are cold to the touch, be mindful of driving or parking vehicles in tall grass, or otherwise producing sparks or flames.

“We’ll take all the rain we can get, but based on all the variables and inputs that go into describing fire danger, we are still sitting at a ‘high’ fire danger rating,” Cernicek said. “That should mean something to all of us.”