25 Years Later, Wyoming Still Grapples with Legacy of Matthew Shepard’s Murder

Despite progress, some in the LGBTQ+ community fear for future

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Oct 12, 2023

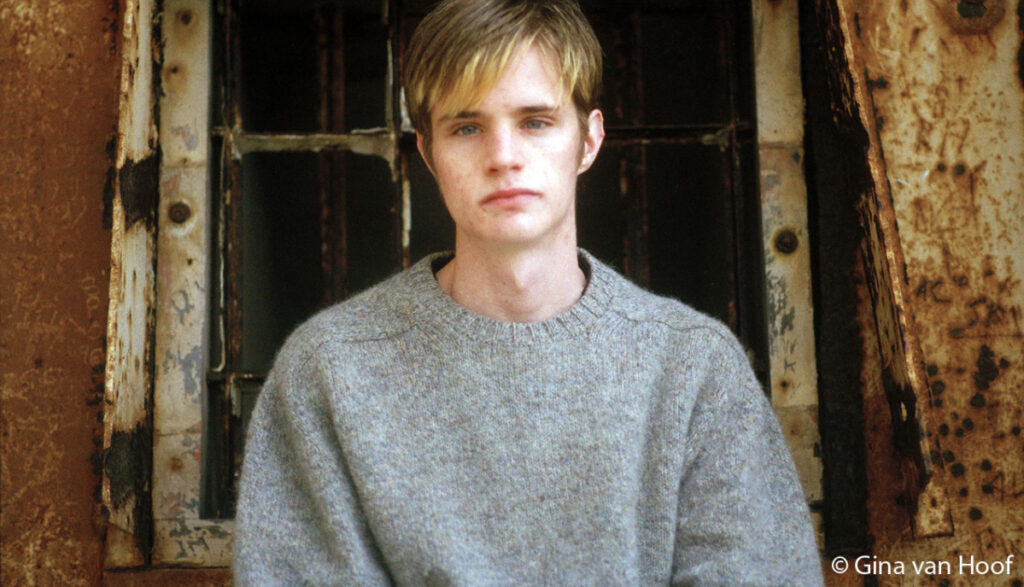

Twenty-five years ago today, 21-year-old Matthew Shepard died from injuries he suffered in one of the most shocking anti-gay hate crimes in U.S. history. Wyoming is still reeling from the incident. (AP Photo/Ed Andrieski, File)

By Jacob Gardenswartz

Special to the Wyoming Truth

This story was updated as of Oct. 13, 2023, at 1:10 p.m. MT.

Chance remembers the exact moment he first learned about Matthew Shepard.

He was just five years old when the 21-year-old University of Wyoming student’s murder shocked the world in 1998, prompting new conversations about anti-gay hate crimes and catalyzing the movement to expand protections for LGBTQ+ people.

It wasn’t until middle school that he fully understood what happened.

“I was on the beach with my dad,” Chance recalled in a recent interview. “I don’t know how the subject got brought up, but he’s like, ‘You know, there’s this guy named Matthew Shepard who was killed because he was gay.’”

“I remember I said, ‘Who would do a thing like that?’ And my dad says, ‘I think the people who killed him… they felt very insecure, and they felt very afraid because he was different. And so they thought that by getting rid of the problem, it would make things better.’”

Chance then identified as a lesbian and was growing up on the East Coast. Now living as a transgender man in Cheyenne, he asked the Wyoming Truth to withhold publishing his last name, for fear of being targeted for his gender identity.

“I just remember being like, ‘Damn, I never want to live there,’” Chance mused of his initial reaction to Shepard’s story. He added with a chuckle, “That didn’t age well.”

For the past 25 years, Wyoming has grappled with the infamy of Shepard’s murder. Once known to most Americans for its cowboy culture and scenic landscapes, the state was transformed overnight to represent the face of homophobic violence, sparking a resurgence of the gay rights movement that would go on to force political and social changes at an unprecedented pace.

Yet within Wyoming today, opinions are mixed as to how much progress has really been made.

“Wyoming is the Equality State — and we’re the Matthew Shepard state,” said Rep. Dan Zwonitzer (R-Cheyenne), the only openly-gay lawmaker serving in the state legislature. “Have we come that far, politically or legislatively, since Matthew Shepard’s death in Wyoming? No, probably not. But I still feel like, behind the scenes, [we are] helping the collective conscience of the state be more accepting.”

But some members of the LGBTQ+ community — especially transgender Wyomingites — fear a backlash is brewing. They point to the slew of anti-trans bills debated in the legislature this year, and the GOP movement to restrict LGBTQ+ rights more broadly, as evidence of the state’s backsliding attitudes.

“It is very difficult for queer people in Wyoming,” said Santi Murillo, a transgender woman and spokesperson for Wyoming Equality, the only statewide LGBTQ+ advocacy organization. “I feel like people here don’t have a problem as long as it’s, like, kept a secret.”

Some are content maintaining such secrecy.

“I kind of keep my head low,” said Chance. “People who need to know about me know about me. But people who don’t need to know about me don’t know about me—and that’s none of their business.”

Others, however, have been more vocal about their identities — and paid a price for it. UW student Artemis Langford, a transgender woman, has been the subject of lawsuits and verbal attacks for joining a sorority last fall.

In September, three out-of-state activists wrote anti-trans messages on rocks scattered throughout campus, sparking fears that history could soon repeat itself in Laramie.

“Back then, nobody knew the lead up,” Murillo recalled of Shepard’s murder. “People were like, ‘Oh, we never saw this coming,’ and ‘How could this happen?’”

“Right now, what we’re witnessing here, this is how those horrible tragedies happen,” Murillo warned. “It’s just heartbreaking.”

A ‘senseless, brutal, terrible thing’

The story of Matthew Shepard’s death has been told in news media, books, plays and documentary films.

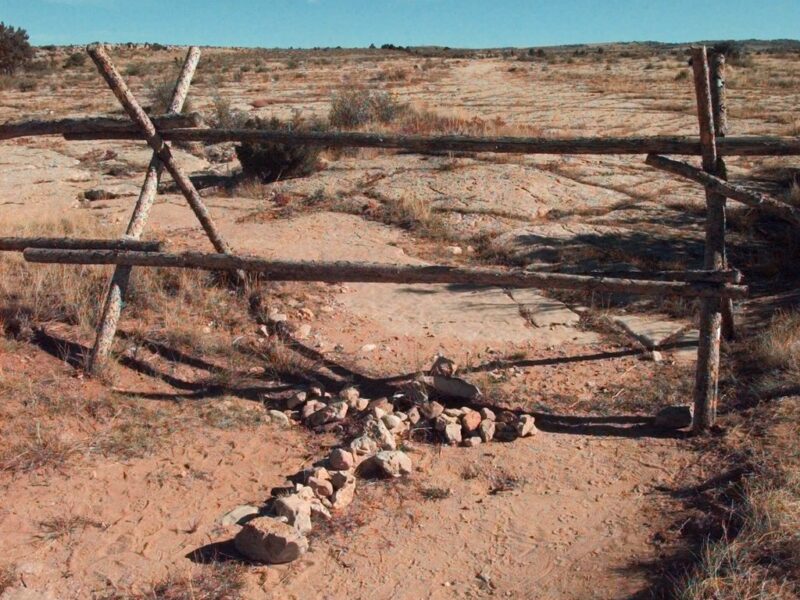

On Oct. 6, 1998, Shepard was approached by two men in their early 20s — Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson — at a bar in Laramie. Shortly after midnight the next morning, they offered to drive Shepard home. Instead, they drove west, robbing Shepard, tying him to a fence, beating him with a pistol and leaving him for dead. He wasn’t discovered until around 6 p.m. the following evening, still alive but so bludgeoned that the cyclist who spotted him initially thought he was a scarecrow.

Shepard was taken to Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins, Colorado. He died from his injuries on Oct. 12—25 years ago today.

In the murder trial of McKinney and Henderson, prosecutors and the defense sparred over whether Shepard was explicitly targeted because of his sexuality.

Kristen Price, McKinney’s girlfriend who herself faced charges tied to the attack, testified that the two men “pretended they were gay to get [Shepard] in the truck and rob him.” Defense attorneys later attempted to invoke a so-called “gay panic” defense, suggesting McKinney was driven to temporary insanity due to unwanted sexual advances Shepard allegedly made. Ultimately, both men were convicted of the murder and sentenced to two consecutive life sentences.

Conflicting accounts have since emerged about whether Shepard’s sexuality actually motivated the crime, or if other matters could have contributed. In 2004, Price told ABC News she lied to police about her boyfriend’s motivation, while the two convicted killers told the outlet the attack was motivated by money and drugs. A 2013 book by journalist Stephen Jimenez — the producer of that ABC News segment — later suggested Shepard and McKinney had occasionally been intimate, concluding the Wyomingite’s murder was actually a result of a dispute over methamphetamine.

But such claims were undercut by the killers themselves. They told theater artists behind “The Laramie Project” — an award-winning play based on verbatim interviews with Laramie residents in the aftermath of the attack — they targeted Shepard because he was gay.

“Matt Shepard needed killing,” McKinney is said to have confessed to one of the play’s creators in a 2009 update to the drama. “The night I did it, I did have hatred for homosexuals.”

Around the country, the reaction to Shepard’s death was widespread. “It was a senseless, brutal, terrible thing,” former U.S. Sen. Alan Simpson (R-Wyo.) told the Wyoming Truth. He was in Laramie at the time of the attack, and later participated in a vigil at the U.S. Capitol, where he faced boos from the audience.

“I said, ‘Just shut up. Don’t boo me. I’m as appalled as you are,’” recalled Simpson, who had retired from elected office in 1997. “This is not a Wyoming values thing. This is a cruel, evil thing of the first order.”

Also present for the vigil was former Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.), the first member of Congress to voluntarily come out as gay and the only openly-gay lawmaker serving in Washington at the time.

“My reaction, to be honest, was to use this to show people how we had to keep up the fight,” Frank told the Wyoming Truth in an exclusive interview. “I was obviously saddened by what happened to Matthew Shepard. But it was also a sort of a teaching moment for the rest of the country — to point out that this is one of the things that prejudice leads to.”

Frank immediately began work on legislation to expand hate crime protections at the federal level. States around the country did the same.

But in Wyoming, lawmakers failed to institute any legislative changes. The state is now one of just three without a hate crimes law on the books.

“I thought about bringing one, but it just never seemed like the politics were never there,” said Zwonitzer, who began serving in 2005.

“It got more and more awkward as every other state passed a hate crimes law,” he noted, but ultimately, “it was just easier to leave it sitting on the sidelines and work on other issues.”

In Congress, efforts to enact hate crimes legislation stalled for over a decade. But in 2009, after Democrats regained control of all branches of government for the first time since Shepard’s death, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act was passed. Named in honor of Shepard and Byrd Jr., a Black man killed by white supremacists in Texas the same year as Shepard, the measure extended federal hate crime protections to cover sexual orientation, gender identity and disability. It also made it easier for the government to bring such charges.

Frank, who presided over the House as it took up the vote on final passage, recalled difficulties uniting the Democratic caucus behind it. While most Democratic lawmakers supported the bill — House Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) said in a statement to the Wyoming Truth it “stands as a pillar of safety and justice for every America” — some Black lawmakers in the South had received concerns from ministers in Black churches, who feared the law might enable prosecutions for preaching anti-gay scripture.

Frank took on the matter directly: “I addressed the Democratic caucus and said, ‘Look, let me be very clear: this is only about physical violence and things that are otherwise criminal,’” he recalled.

“‘Let me put it to you this way,’” he continued. “‘As Chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, if this bill becomes law, it will still be entirely legal to call me a fag. I just wouldn’t recommend it to people in the banking business.”

The bill passed with primarily Democratic support in both the House and Senate. Yet all three of Wyoming’s elected officials in Washington opposed the measure.

Neither Sens. John Barrasso (R-Wyo.) nor Cynthia Lummis (R-Wyo.) — who served in the U.S. House in 2009 — responded to the Wyoming Truth’s questions about Shepard’s murder and the subsequent legislation.

The price of progress

There’s no denying Wyoming is more accepting towards gays and lesbians than it was a quarter century ago.

In Laramie, pride flags hang in windows and posters declare that “hate has no place here.” There are still no gay bars in Wyoming, but UW has a LGBTQ+ resource center that helped organize a week of programming commemorating the anniversary of Shepard’s death.

Lummis surprised many when she broke ranks last year to become one of just 12 Republican Senators supporting a law enshrining same-sex and interracial marriage protections, a vote which earned her censure by Wyoming GOP leaders.

On the whole, though, Wyoming has maintained a hands-off approach to LGBTQ+ issues, Zwonitzer argued, allowing gay people to live peacefully so long as they don’t rock the boat.

“The understood agreement is, ‘If we don’t push it too hard forward, you know, we won’t push it too hard back on you,’” Zwonitzer said. “The mantra for a long time in Wyoming — up until this year — is that we never really took a step forward on LGBT rights, but we never took a step back.”

The legislative session this year was different. Lawmakers debated a slew of anti-LGBTQ+ bills, including measures to limit gender-affirming health care for youth, ban discussions of sexual orientation and gender identity in the classroom and preclude transgender students from participating on sports teams aligned with their gender identity. Ultimately, only the transgender sports ban passed, which Zwonitzer claimed was significantly watered down from initial versions.

Still, anti-trans sentiment remains widespread throughout the state GOP. And in Washington, Wyoming Rep. Harriet Hageman has emerged as a top voice in anti-trans debates, co-sponsoring a federal measure to ban gender-affirming healthcare for youth and describing gender transition surgeries as “sexual lobotomies.” Her office did not respond to the Wyoming Truth’s questions about how Shepard’s story informs her views of LGBTQ+ issues.

“We’re back to the point where to be a Republican, you have to be kind of generally anti-LGBT,” said Zwonitzer.

But he still maintains optimism: “I think we’ll get past it. It’s just another political cycle we’re going through.”

Frank, too, was optimistic about the future. “Prejudice is defeated by reality,” he said. “As gay people spoke out and people saw that the nasty stereotypes and bigotry was wrong, we won. The problems come when you stop simply allowing prejudice to survive and confront it… The fight now is a product of progress.”

The ‘trans panic’ and the ‘high blue sky’

That doesn’t make things any easier for those living through the current backlash.

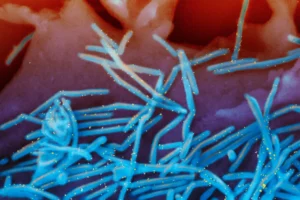

National data shows anti-gay violence is still widespread. A 2022 study by researchers at UCLA’s Williams Institute found LGBTQ+ people were nine times more likely to be victims of violent crime than their straight peers. In 2018, University of Pennsylvania student Blaze Bernstein was killed near his home in Southern California by a man who allegedly targeted him because he was gay and Jewish.

“It’s just very frustrating for me as a parent of somebody that faced such hardship because of the world that he lived in,” Bernstein’s mother, Jeanne Pepper-Bernstein, told the Wyoming Truth.

She said Shepard’s parents, Judy and Dennis, were among the first to reach out after their son’s murder to provide comfort and support. But speaking this week, she did not share the lawmakers’ optimism. “To see that things have continued to go backwards since then, it’s just very sad for me,” Pepper-Bernstein said.

Some have suggested that growing political polarization has contributed to the rise in anti-LGBTQ+ sentiments. Leigh Fondakowski, head writer of “The Laramie Project,” recalled that she and her team were “generously welcomed into that town” when they first set out to document the aftermath of Shepard’s death.

“I’m not sure that would happen now,” she remarked in a recent interview with the Wyoming Truth. “I’m not sure what would happen if a group of New York theater people went to a small town in a red state.”

Murillo fears the current climate only serves to push LGBTQ+ folks out of Wyoming. “A lot of my friends who I went to college with who are queer, they all left,” said Murillo, who must travel to Denver for trans health care services, lacking any viable options within the state. “We don’t have those resources, and we don’t have those hate crime laws. People are afraid to be themselves here.”

Still, she and others spoke longingly about what Wyoming could be, about what Wyoming really is — a place to escape fast-paced city life and embrace the beautiful wilderness.

“Wyoming is not a people who are filled with evil,” Simpson stated. “On a day like this, it’s 70 degrees and the high, blue sky and they’re not thinking about putting cruelty to people or who you stay with or who you love.”

“I moved to Wyoming because of how beautiful it is,” Chance echoed. “I didn’t move here for the politics. I didn’t move here to go to school. I didn’t move here, you know, because of the people. I moved because it’s beautiful, and I want to ride my horse and watch eagles soar across the sky.”

Chance paused, his deep voice quivering as he struggled to find the right words.

“That’s what keeps me here,” he said softly. “I’m still here. I’m still happy. But I’m also still careful.”