Indigenous Motorcyclists Ride for Their Stolen Sisters

Bikers converge on Sturgis rally to raise funds, awareness for missing and murdered native women

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Aug 02, 2023

A member of Medicine Wheel Ride pours sand in the cracks of the pavement outside the Wind River Casino on July 31 to call for an end to violence against Indigenous women. (Wyoming Truth photo by Jennifer Kocher)

By Jennifer Kocher

Special to the Wyoming Truth

RIVERTON, Wyo.—The women crouched in their black leather chaps and jackets outside the Wind River Casino Monday night, clutching small cups filled with red sand. As the sun slipped behind the Wind River Mountains, they silently poured the sand into the gaping seams of the parking lot.

It’s more than just a symbol. For these Indigenous motorcyclists, it’s a commitment to actively advocate for an end to violence against Native women. They are part of Medicine Wheel Ride, a national nonprofit comprised of over 200 women, who have come from across the country to ride to the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally in South Dakota in honor of missing and murdered Indigenous women and people.

Each has her own story to tell about a missing sister, aunt, daughter or mother for whom they ride. These 14 women left Phoenix, Arizona, on Saturday in 117-degree heat. They stopped in Riverton on July 31 to pick up Corrine Tuma, 61, and will join others along their five-day trip through Arizona, Wyoming, Montana and South Dakota.

Co-founder Lorna Cuny said Medicine Wheel Ride is about trying to affect meaningful change. They chose the 10-day Sturgis rally as their destination, because it’s largely a gathering of white men, and it draws hundreds of thousands of riders and tourists annually to the Black Hills region of the United States.

“We want to make an impact,” Cuny said. “We’re trying to get word out to reach as many people as possible. There are people from all over the country who have never heard of MMIW [murdered and missing Indigenous women].”

The cyclists also want to take a stand against the violence that, in many cases, is being perpetrated by non-native men. According to a report by the National Congress of American Indians, an average of 67% of rapes or sexual assaults against Native women were committed by non-natives, most of whom were never brought to justice.

The Sturgis rally also has a history of sex trafficking with several arrests made each year. Between 2013 and 2022, over 70 people were arrested for sex trafficking, according to figures from the nonprofit advocacy group Native Hope.

Cuny, an Oglala Lakota tribal member who grew up on the Pine Ridge Reservation but now lives in Rapid City, South Dakota, said the group was formed in 2019 by five strangers who met online and shared stories about domestic violence and missing and murdered Indigenous women.

For Cuny, it was her sister, Susan Lacee Fast Eagle-Chief Eagle, 30, who disappeared from Rapid City in May 2021.

The statistics speak for themselves. In 2021, The FBI reported 5,203 missing Indigenous girls and women. In Wyoming, 216 Indigenous people were reported missing from nine Wyoming counties, some of them more than once, between 2021 and 2022, according to the Wyoming Survey and Analysis Center. In 2022, Indigenous people accounted for 12% of homicide victims in Wyoming. The Indigenous homicide rate was 18.3 per 100,000 citizens, which is nearly six times higher than the homicide rate for white victims, according to the same report.

“We deserve to take up space here,” said Luvy Yonnie, another founding member of Medicine Wheel Ride. “We ride for awareness and to support families who have lost loved ones.”

‘We Ride for Her’

Tuma, who is Navajo and lives in Riverton, has participated in the Medicine Wheel Ride for the past three years. She rides in honor of 23-year-old Jade Wagon, a daughter of her friend Nicole Wagon, whose body was discovered in a field on the Wind River reservation in 2020.

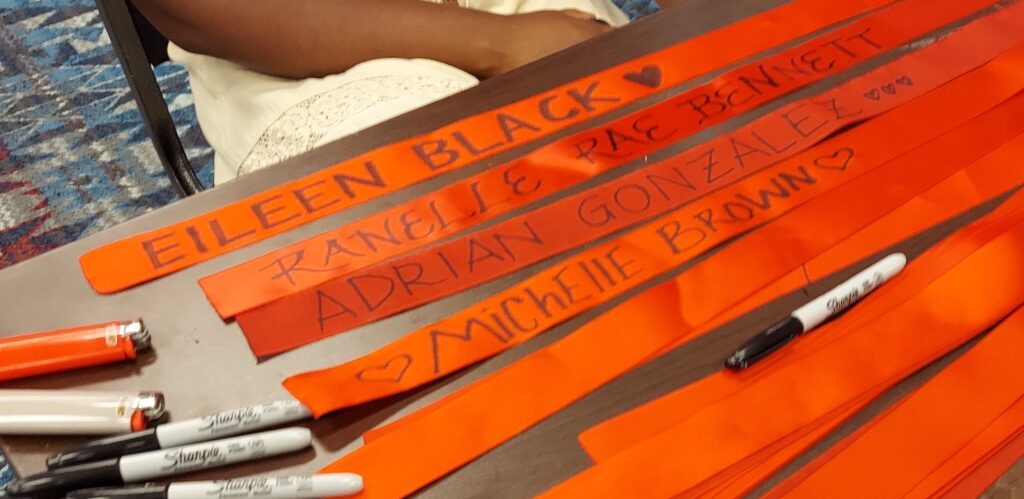

The names of the missing and murdered women are written on red ribbons that dangle from the backs of the motorcycles. The women all wear patches on the backs of their jackets that read: “No more stolen sisters.”

The group also raises money through fees, sponsors and donations to help families search for missing loved ones and pay for funeral expenses or legal fees to as they seek justice, Cuny said.

This year, the motorcyclists also are traveling with a film crew and employees of the Connecticut-based nonprofit Red Sand Project, which helped fund the documentary, “We Ride for Her.” The 19-minute film follows the group’s 2022 journey and chronicles their stories of loss and quests for justice.

“The reality of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and relatives is a horrific one with its origins in the violence brought upon Indigenous communities by colonizers,” Prairie Rose Seminole, one of the film’s stakeholders, said in a statement about the film. “A history of violence and devaluation of Native bodies, combined with a justice system that was never established to protect Indigenous people, created the epidemic we see today.”

The documentary, which will be released in 2024, will be shown at nine stops along the 10-day route, including Riverton.

“We need to be visible,” Tuma said. “We make this journey for a purpose, and we’re here to support each other.”