Vast Number of Wyoming Judges Served as Prosecutors, Wyoming Truth Survey Shows

Higher percentage of sitting Wyoming judges with prosecutorial background compared to national average, raising questions about the handing down of justice

- Published In: Criminal Justice

- Last Updated: Aug 05, 2022

Every sitting Wyoming Supreme Court judge had only private practice experience before being appointed to the high state court. (Courtesy photo from Amy Richards, Townsquare Media)

By Yaritza Castrejon, Gabrielle Despain, Nicholas Espenan and Clay Simpson

Special to the Wyoming Truth

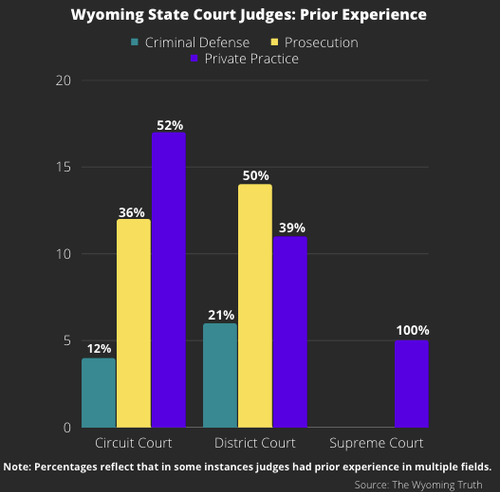

Nearly half—45%—of judges in Wyoming served as prosecutors before they took the bench, according to a Wyoming Truth survey and analysis of all 57 circuit, district and state supreme court judges in the state.

By contrast, 36% of all federal court judges served as prosecutors, almost 10 percentage points lower than the number of judges in Wyoming who served as prosecutors.

While 17.5% of Wyoming judges worked as public defenders, only 8% of the federal court judges did so.

Given that such a large swath of Wyoming judges have a prosecutorial background, how does this affect the meting out of justice in the Cowboy State? Is justice truly blind? Or does the judges’ professional experience prompt them to rule with a heavier hand when issuing decrees from the bench?

Buttressing this concern is that the United States leads the world with the highest rate of incarceration—2 million people are behind bars, which represents roughly 25% of the global prison population, according to the Word Population Review.

The adult incarceration rate in Wyoming stands at 850 per 100,000 residents—35.14% higher than the national average, the Prison Policy Initiative reported.

And when it comes to juvenile incarceration, Wyoming ranks third in the nation behind only Alaska and West Virginia, with a rate of 239 per 100,000 juveniles—110% above the national average, data from Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center shows.

Wyoming judges have been shaped by their legal experience beyond prosecution and criminal defense work, the Wyoming Truth survey shows. More than half of the judges—57.9%—worked in private practice, and nearly a quarter, 24.6%, bring a combined background as a public defender or prosecutor and private practitioner.

The Wyoming Truth survey also found that: during their tenure in private practice, 12.2% of Wyoming judges were employed by family law and general practice firms; 10.2% practiced personal injury, real estate, estate planning, criminal and business law. And 8.2% of the judges practiced civil law, and 4.1% practiced contracts and natural resource law.

Wyoming’s 57 judges are appointed to fill vacancies on the circuit, district and state supreme court through what is called a merit-based selection system.

“The Judicial Nominating Commission screens and interviews applicants and sends the three best candidates to the governor who must choose from that list,” said Sharon Wilkinson, executive director of the Wyoming Bar Association.

Chief Justice Kate M. Fox of the Wyoming Supreme Court, a gubernatorial appointee to the commission, agreed. “The commission cares about the kind of person the judge is,” she said in an interview for this story. “This isn’t just about the law–it’s about human beings.”

Jonathan Gerard, a Lander-based criminal defense attorney, said he believes sentencing cuts both ways—and really comes down to the individual judge.

“Public defender judges can oftentimes be more difficult to deal with,” Gerard said in an interview with the Wyoming Truth. “They don’t want to be seen as biased and may spend a few years swinging in the other direction. Sometimes prosecutor judges are more fair and give less sentencing. Most focus on sentencing guidelines, while some may focus on community expectations.”

But some criminal defense attorneys in Wyoming remain frustrated that the state exceeds the national average for judges with prosecutorial backgrounds.

Crystal Stewart, a criminal defense lawyer with Pence and MacMillan, LLC in Cheyenne, said she is concerned about potentially unfair bond conditions and harsher sentencing.

“I think if we had a more diverse set of judges in Wyoming—meaning more [with] criminal defense backgrounds, then there would be better treatment of criminal defendants, lower sentences of incarceration and more opportunities for criminal defendants to get the outside mental health or addiction treatment they need,” she said.

Judicial diversity has become a national issue. In March last year, 21 advocacy organizations, including the American Association for Justice and the National Employment Law Project, submitted a letter to Rep. Hank Johnson (D-Ga.), chair of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property and the Internet, as part of its hearing on “The Importance of a Diverse Judiciary.”

The members wrote that judges from underrepresented legal backgrounds “are better equipped to understand the experiences of each litigant before them, to recognize the disparate burdens that laws often place on people who are living with low incomes or otherwise marginalized, and to render more informed decisions, including on civil and human rights, reproductive rights, and economic justice.”

Stewart said: “I don’t know if there is really any solution to the issue other than to get more defense-minded people appointed as judges. But that still requires defense attorneys to apply, and I don’t think there are a lot who apply for judgeships.”