Widows and Widowers Group Offers Grassroots Solution to Global Health Concern

As loneliness becomes increasingly prevalent, and potentially deadly, Cheyenne residents access options in their own backyard

- Published In: Other News & Features

- Last Updated: Dec 23, 2023

Vicki Ivey and Richard Randall take a trip down memory lane, as they flip through a Cheyenne Widows and Widowers photo album. (Wyoming Truth photo by David Dudley)

By David Dudley

Special to the Wyoming Truth

CHEYENNE, Wyo.—Richard Randall remembers dancing at parties with his late wife.

“She was Puerto Rican,” he said. “We’d throw parties and dance the merengue with our friends and family late into the night.”

The couple was married for 24 years when Lydia, then 69, died from cancer in 2013 on the day after Christmas. Randall quit dancing.

“She was my wife and my best friend,” said Randall, 74, a retired engineer’s aide for the Wyoming Department of Transportation. “After she died, I found myself alone. Really alone. I didn’t know what to do.”

Loneliness and confusion often accompany the grief process for widows and widowers of all ages. But new studies show that extreme isolation, especially for older adults, may be dangerous.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared loneliness to be a serious threat to global health. And U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy equated the health impacts of extreme loneliness to smoking 15 cigarettes a day in an advisory released in May.

Murthy’s research found social isolation led to a 29% increase in risk for developing heart disease, a 32% increase of risk for stroke and, especially in older adults, a 50% increase of developing dementia. But the most alarming finding linked chronic loneliness with self-harm and suicide—the probability of which doubled for men who lived alone and led to increased incidences of hospitalization due to self-harm for women.

Seen through that lens, Wyoming’s vast expanses of open space may take on a darker light: Wyoming was named the loneliest state per capita in a survey released in June by The Roots of Loneliness Project.

For Wyomingites reeling from the death of a spouse, loneliness may be exacerbated by grief, which can lead to a sense of not belonging, according to clinical psychologist Marnin J. Heisel.

“Widows and widowers can feel like a burden to loved ones,” said Heisel, a professor at the University of Western Ontario, in London, Ontario, Canada, whose work focuses on promoting psychological resiliency and preventing suicide in older adults. “They sometimes feel as though nobody understands what they’re going through, which can lead to despair and even increased incidences of suicidal ideation.”

But groups like Cheyenne Widows and Widowers (CWW) may offer a glimmer of hope. Driven by loneliness, and the need to meet people who are wrestling with similar challenges, Randall joined the group. Twelve years on, he’s happy he did.

“I really needed to get out of the house and socialize,” said Randall. “It’s because of them that I don’t have to live like a hermit with a shotgun laid across my lap.”

Ahead of their time

Founded in 1999, Cheyenne Widows and Widowers offers community to those who need it most. The group, which has 27 active members aged 55 to 85, initially gathered at eateries around town. As it evolved, members saw plays and movies together; more recently, they began taking classes on natural history at the Wyoming State Museum.

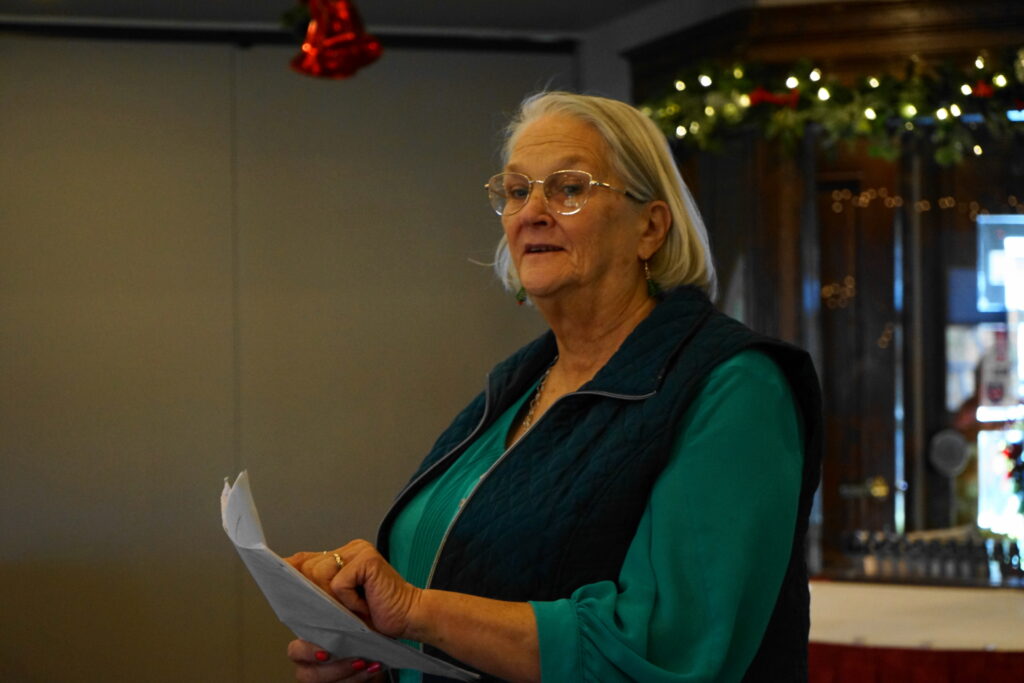

Vicki Ivey, the group’s current leader, joined in 2014 after the death of Dale, her husband of 54 years. As with Randall, who joined around the same time, the meetings and outings filled a pressing need for Ivey.

The Iveys raised three children and moved to Cheyenne in 1992 when Dale retired from his job as oil field foreman for Phillips Petroleum Company. Their adult children had jobs and families of their own by then. Ivey wasn’t ready for the intense feelings of loneliness that followed Dale’s passing.

“Dale was always shy and introverted,” said Ivey, 82. “When he died, I didn’t have any friends in town—nobody to talk to or do anything with.”

So Ivey went to a meeting and never looked back. She befriended Patricia “Trish” Meares, 85, and their relationship deepened over the years. In March 2022, when Ivey was diagnosed with an aggressive form of uterine cancer and needed a ride to chemo treatments—six of them spread over 18 weeks, lasting four hours each—Meares was behind the wheel.

‘I chose life’

Meares accompanied Ivey to chemotherapy treatments because she didn’t want her friend to battle cancer alone. And both needed a social engagement on their calendars.

“Having something to look forward to is key to fighting loneliness,” said Meares. “And, as I learned, it’ll keep you alive.”

Meares married her husband, Steve, in 1971, and they raised a son and daughter who were active in scouting. The couple befriended other parents who were equally involved in their children’s activities, so their home was always abuzz. Even after their children were grown, the Meares enjoyed a full social calendar with family and friends.

But that changed in 2009, when Koreen, the Meares’s youngest daughter, succumbed to complications during an operation. Two years later, Steve suffered a stroke and died.

“I can’t even begin to tell you how hard it is to lose the person you’ve lived with for 40 years,” said Meares. “It’s devastating.”

Meares didn’t feel alone at the funeral, because she was surrounded by family and friends. It wasn’t until after the funeral that her new reality set in.

“I had nowhere to go, nobody to talk to,” Meares said. “I was really in a bad way. I considered suicide. I felt as though I had no purpose in life. So, I thought about ending it.”

But three things stopped her.

“First, I was too chicken to go through with it,” Meares said. “Second, I couldn’t bear the thought that I would put my children [including three from a previous marriage] into the same situation. I couldn’t do that to my kids.”

After wrestling with those thoughts for a year, Meares gave herself a “hard kick in the ass.” She joined the support group in 2013 and something clicked.

Which happens often, said Heisel.

“Members of our communities offer the strongest connection and [support] for others who are struggling,” said Heisel. “That’s one of the reasons why, in the United Kingdom, doctors will ask their older patients how they’re doing. If they’re feeling lonely, and depressed, the doctor will write a prescription that says ‘Join a social group.’”

Meares agreed, saying that joining the support group saved her life.

“They showed me that you can’t live in grief,” said Meares. “You’ve got to go beyond grief. You’ve got to find things to live for, make new friends. You’ve got to plan for things and look forward to them.”

“Because of that,” she added after a pause, “I chose life.”

Cheyenne Widows and Widowers is free and open to anyone who wants to join. The group meets at the Laramie County Public Library every Tuesday at 12:30 p.m.